I.

Textual History

In the early spring of 1798, William Erskine met M.G. Lewis,

author of the popular and notorious Gothic novel The Monk (1796), and

showed him two poems from his friend, Walter Scott, translations of Gottfried

August Bürger’s “Lenore” (entitled by Scott

“William and Helen”) and “Der Wilde Jäger” (“The Chase”).

Impressed by these ballads, Lewis invited Scott to contribute to his collection

of supernaturalist ballads, originally planned to be

entitled “Tales of Terror.” This arrangement led to a period of close

collaboration between Scott and Lewis that is detailed in eleven letters from

Lewis to Scott from June 1798 to May 1800 and, retrospectively, in

Scott’s “Essay

on Imitations of the Ancient Ballads” (1830). [For more on what Scott

regarded as his apprenticeship with Lewis, see Section III

of this Introduction.] In the fall of 1799, Scott, frustrated with delays in

the publication of Lewis’s collection, met with his old school friend James Ballantyne and devised a plan that would lead to the

limited publication of An Apology for Tales of Terror. J.G. Lockhart’s Life

of Scott tells the story of this meeting, which led to Scott’s long

professional relationship with Ballantyne, the

printer of most of Scott’s voluminous literary output:

Mr. Ballantyne had

not been successful in his attempts to establish himself in that branch of the

law, and was now the printer and editor of a weekly newspaper in his native

town. He called at Rosebank one morning, and requested

his old acquaintance to supply a few paragraphs on some legal question of the

day for his Kelso Mail. Scott complied; and carrying his article himself

to the printing-office, took with him also some of his recent pieces, designed

to appear in Lewis’s Collection. With these, especially, as his Memorandum

says, the “Morlachian fragment after Goethe,” [1] Ballantyne was charmed, and he expressed his regret that

Lewis's book was so long in appearing. Scott talked of Lewis with rapture; and,

after reciting some of his stanzas,  said “I ought to apologise to you for having troubled you with anything of

my own when I had things like this for your ear.” “I felt at once,” says Ballantyne, “that his own verses were far above what Lewis

could ever do, and though, when I said this, he dissented, yet he seemed

pleased with the warmth of my approbation.” At parting, Scott threw out a

casual observation, that he wondered his old friend did not try to get some

little booksellers’ work, “to keep his types in play during the rest of the

week.” Ballantyne answered, that such an idea had not

before occurred to him—that he had no acquaintance with the Edinburgh

“trade;” but, if he had, his types were good, and he thought he could afford to

work more cheaply than town-printers. Scott, “with his good humoured

smile,” said, “You had better try what you can do. You have been praising my

little ballads; suppose you print off a dozen copies or so of as many as will

make a pamphlet, sufficient to let my Edinburgh acquaintances judge of your

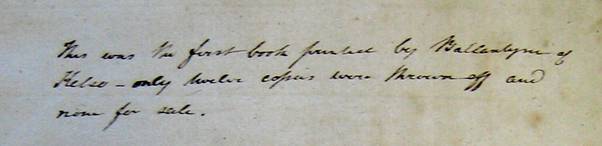

skill for themselves.” Ballantyne assented; and I

believe exactly twelve copies [2] of

William and Ellen, The Fire-King, [3]

The Chase, and a few more of those pieces, were thrown off accordingly, with

the title (alluding to the long delay of Lewis's Collection) of “Apology for Tales of Terror—1799.” This first

specimen of a press, afterwards so celebrated, pleased Scott; and he said to Ballantyne “I have been for years collecting old Border

ballads, and I think I could, with little trouble, put together such a

selection from them as might make a neat little volume, [4] to

sell for four or five shillings. I will talk to some of the booksellers about

it when I get to Edinburgh,

and if the thing goes on, you shall be the printer.” Ballantyne

highly relished the proposal; and the result of this little experiment changed

wholly the course of his worldly fortunes, as well as of his friend’s. (1: 275-76 )

said “I ought to apologise to you for having troubled you with anything of

my own when I had things like this for your ear.” “I felt at once,” says Ballantyne, “that his own verses were far above what Lewis

could ever do, and though, when I said this, he dissented, yet he seemed

pleased with the warmth of my approbation.” At parting, Scott threw out a

casual observation, that he wondered his old friend did not try to get some

little booksellers’ work, “to keep his types in play during the rest of the

week.” Ballantyne answered, that such an idea had not

before occurred to him—that he had no acquaintance with the Edinburgh

“trade;” but, if he had, his types were good, and he thought he could afford to

work more cheaply than town-printers. Scott, “with his good humoured

smile,” said, “You had better try what you can do. You have been praising my

little ballads; suppose you print off a dozen copies or so of as many as will

make a pamphlet, sufficient to let my Edinburgh acquaintances judge of your

skill for themselves.” Ballantyne assented; and I

believe exactly twelve copies [2] of

William and Ellen, The Fire-King, [3]

The Chase, and a few more of those pieces, were thrown off accordingly, with

the title (alluding to the long delay of Lewis's Collection) of “Apology for Tales of Terror—1799.” This first

specimen of a press, afterwards so celebrated, pleased Scott; and he said to Ballantyne “I have been for years collecting old Border

ballads, and I think I could, with little trouble, put together such a

selection from them as might make a neat little volume, [4] to

sell for four or five shillings. I will talk to some of the booksellers about

it when I get to Edinburgh,

and if the thing goes on, you shall be the printer.” Ballantyne

highly relished the proposal; and the result of this little experiment changed

wholly the course of his worldly fortunes, as well as of his friend’s. (1: 275-76 )

The title page

[5] for

this rare book reads as follows:

AN

APOLOGY

FOR

TALES OF TERROR.

— “A THING OF SHREDS AND

PATCHES.” HAMLET. [6]

KELSO:

PRINTED AT THE MAIL OFFICE.

1799.

The scholarly record of the Apology has been vexed by its frequent

confusion with two other texts that have their own share of bibliographical

difficulties [7]:

Lewis’s two-volume collection, finally published in December of 1800 under the

title of Tales of Wonder, and Tales of Terror (May, 1801), of

anonymous authorship, although frequently and mistakenly attributed to Lewis. [8] The Apology

contains the following poems that would appear later in Tales of Wonder:

Scott’s translation of Bürger’s “Der

Wilde Jäger” entitled “The Chase” (appearing in Tales

of Wonder as “The Wild Huntsman”); Lewis’s “The Erl-King’s

Daughter” (first appearing in the Monthly Mirror 2 [October 1796]:

371-373), “The Water-King,” and “Alonzo the Brave” (Scott could have

gotten the latter two poems from Lewis himself or from one of the early

editions of The Monk); [9] and Robert

Southey’s “Lord William” (first appearing anonymously in The Morning

Post 16 March 1798; also published in Southey’s Poems [1799]).

Ballads appearing in the Apology not included in Lewis’s collection

include Southey’s “Poor Mary, the Maid of the Inn”

(first appearing in his Poems, 1797); Scott’s “William and Helen” (Lewis

will print instead William Taylor’s famed translation of Bürger’s

“Lenore”); and John Aikin’s “Arthur and Matilda” (from his Poems,

1791).

The text of the Apology used in this edition comes with permission from

the Houghton Library of Harvard (EC8.Sco86.799ta).

Notes:

1. “The Lamentation of the Faithful Wife of Asan

Aga, From the Morlachian Language.” This poem was not

included in either the Apology or Tales of Wonder. Indeed,

despite Lockhart’s reference to Scott bringing with him “his recent pieces,

designed to appear in Lewis’s collection,” only one poem included in the Apology,

“The Chase,” appears in Tales of Wonder (entitled as “The Wild

Huntsman”). The nine poems included, almost certainly suggested by Scott,

comprise a representative sampling of the German-influenced “tale of terror”

and its main practitioners at the end of the century. The one name less

known by us today, John Aikin, would have come to Scott’s attention as the

editor of The Monthly Magazine, which published William Taylor’s widely

regarded translation of Bürger’s “Lenore” in 1796.

2. Just five copies of

the text survive today. The four owned by Scott’s library at Abbotsford, the Harvard College

Library, the Morgan Library, and the Huntington Library all carry the

title An Apology for Tales of Terror. A fifth copy, entitled

simply Tales

of Terror, resides at Yale. In his 1894 article for The Edinburgh

Bibliographical Society, “The First Book Printed by James Ballantyne,” George P. Johnston discusses the only two

known copies at the time:

The fifth copy at Yale entitled Tales of Terror

has caused its fair share of scholarly perplexity. Often confused

with Bulmer’s and Bell’s Tales of Terror (London, 1801)—a text of

anonymous authorship that responds to Lewis’s Tales of Wonder—the Yale

copy, once in the private possession of Professor Edward Dowden, is actually

the only one of the five that declares on its title-page “Printed by James Ballantyne.” Aside from its title page, its contents are

identical to the Apology. (Johnston discusses this text in

his “Note to a Paper Entitled ‘The First Book Printed by James Ballantyne.’”) See Ruff’s Yale dissertation for evidence

that the Apology “was not offered for sale” (70-71); among other things,

there exist no advertisements of the volume in the papers, not even in the Scots

Magazine, with its lists of Scottish publications.

A single copy of what George P. Johnston

refers to as the “foreman printer’s copy” (“Note” 90) of the Apology

contains just six poems, ending with “William and Helen” (omitting Lewis’s

“Alonzo the Brave,” Aikin’s “Arthur and Matilda” and

Lewis’s “The Erl-King’s Daughter”); the last ballad

ends on page 57 and page 58 is left blank. This copy was first noted by

W.B. Cook in a Notes and Queries article entitled “The First Work of the

Ballantyne Press” (1874). It now resides at the

Mitchell Library in Glasgow.

Yale has a “negative photostat” of this “foreman

printer’s copy.”

3. Lockhart is wrong on

this score: “The Fire-King” appears first in Lewis’s collection Tales of

Wonder.

4. Scott alludes to Minstrelsy

of the Scottish Border, first edition 1802.

5. The Yale copy’s title page

for its Tales of Terror reads after the quotation from Hamlet:

KELSO:

PRINTED BY

JAMES BALLANTYNE

AT

THE KELSO MAIL PRINTING OFFICE.

__________________________________

1799.

6. From

Act 3.4.93, Hamlet’s calling Claudius a “king of

shreds and patches.”

7. Most notoriously by Henry Morley, who in the introduction

to his edition of Tales of Terror and Wonder (1887) writes mistakenly

that “Lewis published at Kelso, in 1799, his Tales of Terror, and

followed them up in the next year with his Tales of Wonder”(5-6).

8. For

more information on these two texts, see the forthcoming Broadview edition of Tales

of Wonder, edited by Douglass H. Thomson.

9. “The Erl-King’s Daughter” does not appear until the fourth

edition of The Monk, and it is clear from the versions of “The

Water-King” and “Alonzo the Brave” that Scott and Ballantyne

were working from versions of these poems as they appeared in earlier

editions of the novel. See the textual variants

for these poems.

II. The

Scottish-German Connection: “The Unexpected Discovery of an Old Friend in a

Foreign Land”

Scott’s interest in German language and literature stemmed from several key

factors that reflect the overall interest of British writers in the subject

during the 1790’s. In his important “Essay

on Imitations of the Ancient Ballad,” Scott records his

growing personal fascination with such authors as Schiller, Goethe, and

Bürger amid the larger

backdrop of the state of poetry “during the last ten years of the eighteenth

century,” which he claims at that time “was at a remarkably low ebb in

Britain” (23). He cites two early events that first sparked interest in

German writers:

Henry Mackenzie’s presentation of an “Essay on German Literature” to the

Royal Society on April 21, 1788 and his friend Alexander Fraser Tytler’s

translation of Schiller’s Die Räuber in

1792 (Mackenzie’s picture appears at the right). These works alerted

Scott to the “existence of a race of poets who had the … lofty ambition

to spurn the flaming boundaries of the universe, and investigate the realms

of

chaos and old night” (25) and were of special interest in Edinburgh, “where

the remarkable coincidence between the German language and that of the

Lowland

Scottish encouraged young men to approach this newly discovered spring

of literature” (27). Scott records his rather desultory German lessons

under a Dr.

Willich during the winters of 1792-94, while

another decisive event occurred in the summer of 1793, when Anna Lætitia

Aikin Barbauld (portrayed below) “electrified” an Edinburgh literary

society with her reading of a spirited translation of Bürger’s

“Lenore” written by William

appears at the right). These works alerted

Scott to the “existence of a race of poets who had the … lofty ambition

to spurn the flaming boundaries of the universe, and investigate the realms

of

chaos and old night” (25) and were of special interest in Edinburgh, “where

the remarkable coincidence between the German language and that of the

Lowland

Scottish encouraged young men to approach this newly discovered spring

of literature” (27). Scott records his rather desultory German lessons

under a Dr.

Willich during the winters of 1792-94, while

another decisive event occurred in the summer of 1793, when Anna Lætitia

Aikin Barbauld (portrayed below) “electrified” an Edinburgh literary

society with her reading of a spirited translation of Bürger’s

“Lenore” written by William  Taylor

of Norwich, her former student at the dissenting academy in Palgrave, Suffolk.

Although not at the reading, Scott heard of the commotion, found a copy

of Bürger’s ballads, and immediately came up with his own

translation of “Lenore” (entitled “William and Helen”) and, somewhat later,

“Der Wilde Jäger” (“The Chase”),

the two of which, printed in a “thin quarto,” proved to be his first

publication. [1] Supplied

with a copy of Bürger’s ballads and other German

works by his relative Hugh Scott’s wife Harriet, “a young gentlewoman of

high German blood” (Lockhart, Chapter 2) who aided his studies of the language,

Scott tells us he “began to translate on all sides” (“Essay” 43). Most

of these were translations of German dramas, including Goethe’s Goetz

von Berlichingen (later published with Lewis’s aid on March 14, 1799),

but Scott writes that “the ballad poetry, in which I had made a bold essay,

was

still my favorite” (43). From this “German-mad” period, we can also date

Scott’s translation of Goethe’s “Der Erl-König,”

the first poem in An Apology for Tales of Terror. [2]

Taylor

of Norwich, her former student at the dissenting academy in Palgrave, Suffolk.

Although not at the reading, Scott heard of the commotion, found a copy

of Bürger’s ballads, and immediately came up with his own

translation of “Lenore” (entitled “William and Helen”) and, somewhat later,

“Der Wilde Jäger” (“The Chase”),

the two of which, printed in a “thin quarto,” proved to be his first

publication. [1] Supplied

with a copy of Bürger’s ballads and other German

works by his relative Hugh Scott’s wife Harriet, “a young gentlewoman of

high German blood” (Lockhart, Chapter 2) who aided his studies of the language,

Scott tells us he “began to translate on all sides” (“Essay” 43). Most

of these were translations of German dramas, including Goethe’s Goetz

von Berlichingen (later published with Lewis’s aid on March 14, 1799),

but Scott writes that “the ballad poetry, in which I had made a bold essay,

was

still my favorite” (43). From this “German-mad” period, we can also date

Scott’s translation of Goethe’s “Der Erl-König,”

the first poem in An Apology for Tales of Terror. [2]

Scott’s creative engagement with his German source material was a natural

outgrowth of his early fascination with old English and Scottish ballads,

especially of the kind that he read in his beloved Thomas Percy's Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765) and which he

heard and collected in his various excursions in the Border country. In a

note to his “Essay on the Imitations of Ancient Ballads,” Scott draws a

comparison between the old Scottish song of “Patrick Spence” found in Percy and

its German rendering from Johann Gottfried Herder’s highly influential Volkslieder

(1778-1779), [3]

noting close similarities not only in their “vocables

and rhymes” but in their “the turn of phrase” (43 n.1). Scott regarded

this close connection between Scottish and German balladry as “the unexpected

discovery of an old friend in a foreign land” (43 n1). His invoking the German

muse also carried a serious agenda, one shared by the Norwich circle of

ballad-writers Robert

Southey, William Taylor, and Frank Sayers [4]:

Scott felt that “the advancing taste in German language and literature . . . might

easily be employed as a formidable auxiliary to renewing the spirit of our own”

poetry (29), which, we will remember, he considered at a “low ebb” at the

time. James Watt in his study Contesting the Gothic defines a

charged political context for this turn to “ancient” and Gothic source

materials that reveal a close relationship between old British and German

poetry. This connection comprises what Watt calls a “Loyalist Gothic”

from which writers could assert a noble ancient line of British literature in

pointed opposition to enervating French influences. Scott in his “Essay” argues

that the German example could provide an “emancipation from the rules so servilely adhered to the French school”: once relieved from

such “shackles,” the “genius of Goethe, Schiller, and others . . . was

not long in soaring to the highest pitch of poetic sublimity (26).

One can thus understand poems included in An Apology for Tales of Terror

as a small but representative example of the broader movement at the end of the

eighteenth-century to reinvigorate British poetry through the example of the

ancient British and German ballad. Scott’s participation in this movement also

tracks another development that occurs at the turn of the century: the sharp

English critical reaction against Teutonic source materials. From a nation

still at war with France and embroiled in foreign conflict, this literary

import, once promising the revival of a more authentic native idiom, eventually

came to be regarded by some conservative critics as, in the words of Michael

Gamer, “culturally invasive, morally corrupting, and politically jacobin" (144-45) [5]. Scott, warned by

his concerned friends of too close of an association with Lewis and his

combustible Gothic productions, would soon renounce his “German-mad” phase [6].

Having made an “escape” from the “general depreciation of the Tales of

Wonder” (51), Scott goes on to compile a more respectably nationalist

collection of ballads, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802).

Although

the mature Sir Walter Scott would often be critical of German and Gothic

literature, he reveals in his “Essay on Imitations of the Ancient Ballad” just

how formative such influences had been in his decision to embark on a literary

career.

Notes:

1. The

Chase; and, William and Helen. Edinburgh:

Manners and Miller, 1796.

2. In

a letter to his aunt Christian Rutherford in 1797, Scott sent a copy of his “Erl-King” with the following note: “I send a goblin story,

with best compliments to the misses. … I assure you, there is no small

impudence in attempting a version of that ballad, as it has been translated by

Lewis” (Lockhart 1: 239).

3. The Volkslieder

also serves as the primary source for Lewis’s “Danish” and “German” ballads in Tales

of Wonder, and Herder’s "Erlkönigs Tochter" provided the inspiration for Goethe’s “Erlkönig.” Further evidence of the connection between the

German and old British ballad can be found in Herder’s preface to the Volkslieder,

in which he reveals that Thomas Percy's Reliques

of Ancient English Poetry (3 vols., London, 1765) proved the

inspiration for his undertaking. He includes in his collection over twenty

translations from Percy’s collection, besides a number from Allan Ramsay’s Tea-Table

Miscellany (1727) and other volumes of English

and Scottish traditional ballads.

4. For the Norwich

circle’s interest in “incorporating ‘German

sublimity’ into English ballads,” see David Chandler’s “Southey’s ‘German Sublimity’ and Coleridge’s ‘Dutch Attempt.’”

5. For the turn against German-inspired literature,

see Gamer’s Romanticism and the Gothic: Genre,

Reception, and Canon Formation and Peter Mortensen’s British Romanticism and Continental Influences: Writing in an Age of Europhobia.

6. Scott

uses this phrase in a letter to Mrs. Hughes, 13 December, 1827. For Scott’s

turn against his early interests in German and Gothic Literature and his

creation of Sir Walter Scott, champion of the Scottish literary identity, see Gamer’s chapter on Scott in his Romanticism and the

Gothic.

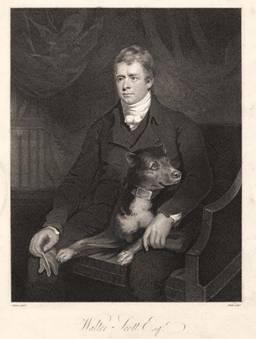

III. Walter Scott and

M.G. Lewis

Scholars

and editors of Walter Scott’s literary works have often been puzzled by

the remarkably high estimate Scott held of Matthew Gregory

Lewis’s

poetic talent. In addition to asserting that Lewis was “the person

who first attempted to introduce something like the German taste into English

fictitious[,] dramatic, and poetical composition” (“Essay” 29), Scott felt

that

“few persons  have exhibited more

mastery of rhyme, or greater command over the melody of verse” (49). While

conceding that Lewis’s The Monk “seemed to create an epoch in our

literature,” Scott’s main interest in the novel was its poetry, and he

went so far as to make the claim, probably a doubtful one, that “the public

were

chiefly captivated by the poetry with which Mr. Lewis had interspersed

his prose narrative” (33). [1]

When Scott agreed to contribute ballads to Lewis’s planned collection of supernaturalist verse, he met with exacting criticism from

what he called his ”Mentor”

(49). A lyrical technician—Scott referred to him as a “martinet” (48)—Lewis

insisted upon scrupulous “accuracy of rhymes and numbers” and, Scott wryly

noted, had some trouble disciplining his “northern recruits” (48). [2] Scott includes

in an appendix to his “Essay on

Imitations of the Ancient Ballad” correspondence from Lewis that reveals

the meticulous, detailed nature of his criticisms and suggested revisions.

Although

somewhat resistant to Lewis’s requested revisions, [3] Scott writes

that “I was much indebted to him, as forcing upon the notice of a young

and careless author hints which the said author’s vanity made him unwilling

to

attend to, but which were absolutely necessary to any hope of his ultimate

success (53-54).

have exhibited more

mastery of rhyme, or greater command over the melody of verse” (49). While

conceding that Lewis’s The Monk “seemed to create an epoch in our

literature,” Scott’s main interest in the novel was its poetry, and he

went so far as to make the claim, probably a doubtful one, that “the public

were

chiefly captivated by the poetry with which Mr. Lewis had interspersed

his prose narrative” (33). [1]

When Scott agreed to contribute ballads to Lewis’s planned collection of supernaturalist verse, he met with exacting criticism from

what he called his ”Mentor”

(49). A lyrical technician—Scott referred to him as a “martinet” (48)—Lewis

insisted upon scrupulous “accuracy of rhymes and numbers” and, Scott wryly

noted, had some trouble disciplining his “northern recruits” (48). [2] Scott includes

in an appendix to his “Essay on

Imitations of the Ancient Ballad” correspondence from Lewis that reveals

the meticulous, detailed nature of his criticisms and suggested revisions.

Although

somewhat resistant to Lewis’s requested revisions, [3] Scott writes

that “I was much indebted to him, as forcing upon the notice of a young

and careless author hints which the said author’s vanity made him unwilling

to

attend to, but which were absolutely necessary to any hope of his ultimate

success (53-54).

While Scott may have benefited from what Lewis called a “severe

examination” of his early ballads (56), the Scottish poet would come to use

the example of his erstwhile mentor’s kind of poetry to define a distinctly

different agenda for his own. In giving reasons for the “general depreciation”

(51) of Tales of Wonder, Scott outlines several factors, including

Lewis’s inclusion of many previously published ballads and the shady dealings

of his publisher Joseph Bell. But Scott also

finds fault with Lewis’s treatment of supernatural themes in terms that

will have a

special resonance for the author of Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.

He objects, as many other critics did, to Lewis’s inclusion of parodies in

his collection of Gothic ballads. This decision to “throw some gaiety into

his

lighter pieces, after the manner of the French writers” in “attempts at

what is called pleasantry” Scott deemed a conspicuous failure (51). We remember

that

opposition to French influence and sophistication comprised one of the

motivating forces in the turn to German sources. With this arch, self-deprecating

consciousness pervading Tales of Wonder, Scott found that ballad

poetry which “had been at first received as simple and natural, was now

sneered at as

puerile and extravagant” (49-50).

Lewis’s distinctly English, very Gothic, and surely “extravagant” treatment of

four old Scottish ballads in Tales of Wonder must have caught Scott’s

attention. These include “Clerk Colvin,” “Willy’s Lady,” “Courteous King Jamie”

[4] and “Tam Lin.” In the

Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, Scott pointedly prints more

authentic Scottish versions of all four poems with the purpose of restoring

their “native simplicity” in opposition to the anglicizing “additions and

alterations” supplied by Lewis (see the head-notes to these poems in the Minstrelsy,

all of which cite Lewis’s earlier example). In an “Introduction” Scott supplies

to an 1806 reprinting of his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, he draws

a strong distinction “betwixt the legendary poems and real imitation of the old

ballads” (cxxxvii). By legendary poems he means a

“kind of poetry … capable of uniting the vigorous numbers and wild fiction,

which occasionally charm us in the ancient ballad, with a greater equality of

versification, and elegance of sentiment, than we expect to find in the works

of a rude age” (cxxxvii). Almost certainly, he is

thinking of the example of Lewis’s poetry. [5] Scott tells us in his

1806 “Introduction” to The Minstrelsy that he designed his first two

original compositions for Tales of Wonder, “The Eve of St. John” and “Glenfinlas,” to furnish, respectively, an example of a

“real” imitation of an “old ballad,” as opposed to the more “modern” legendary

poem “(cxxxvii). This distinction would come to have

great importance for Scott as he goes on to the Minstrelsy and his

project of recovering and championing the Scottish literary heritage. What

seems at first to have been merely a descriptive rubric becomes a charged and

purposeful one, with Scott using the distinction to define his project of

rescuing the authentic and ancient character of the Scottish ballad from modern

and English appropriations of it. [6]

One can see that Scott’s relationship with Lewis, while early in his literary

life and brief, played a fairly significant and complex role in his developing

ideas about poetry. At first a devoted Lewisite, he assigns Lewis the lead role

in the German revival, includes three of his poems in the Apology, and

submits to his mentor’s “severe examination” of his own very first

poems. Warned by his literary friends of the turning tide against Lewis, he

makes his “escape” from the “general depreciation” of Tales of Wonder and,

as he embarks upon his career as literary champion of Scotland, would

come to look back upon his early days as a “German-mad” phase. But Scott

also used the particular character of Lewis’s poetry to define his own. As

opposed to what he regarded as the mannered, modern, and anglicizing language

of Lewis’s Gothic ballad, Scott will aim for a more authentic and native idiom

in his compilation of ancient ballads.

Notes:

1. Scott took the three poems by Lewis

published in the Apology from one of the first three editions of The

Monk. The texts of these poems in the Apology differ from those

Lewis slightly revised for the fourth edition of the novel.

2. Scott’s good friend

John Leyden also contributed to Tales of Wonder with his poem “The

Elfin-King.”

3. Although claiming

“inflexibility” about the revisions (49), Scott generally accepted most of

Lewis’s calls for change. The version of “The Wild Huntsman” that appears in Tales

of Wonder accepts every change called for by Lewis (mainly concerning

rhyme) and thus differs from the earlier version contained in the Apology

(wherein it is entitled “The Chase”). See the textual

variants listed at the end of the poem in Text of the Poems. In

a note to the poem “Frederic and Alice” in his Ballads and Lyrical Pieces (1806),

Scott comments: “It owes any little merit it may possess to my friend Mr.

Lewis, to whom it was sent in an extremely rude state; and who, after some

material improvements, published it in his Tales of Wonder” (143). In

collating the versions of the ballad “Eve of St. John” as published

independently in Kelso in 1800 and as it appeared in Tales of Wonder,

John William Ruff notes that, if anything, Scott took pains to “polish” the

poem and “make his meter smoother” for its inclusion in Lewis’s collection

(175). On the other hand, Scott ignores the lengthy list of suggested

revisions—what Lewis called a “severe examination”—for “William and

Helen” (see “Appendix” to the “Essay” 54-56).

4. Entitled “King Henrie” in the Minstrelsy.

5. Both Coleridge and Southey also regarded

Lewis as modernizing the ancient ballad. In his appraisal of the poetry in The

Monk, Coleridge wrote that “The simplicity and naturalness

is his own, and not imitated; for it is made to subsist in congruity with a

language perfectly modern, the language of his own times. … This, I think, a

rare merit” (Griggs 1. 379). Southey takes issue with Lewis on just this point:

“In all these modern ballads there is a modernism of thought and

language-turns, to me very perceptible and unpleasant. … He is not versed

enough in old English” (C. C. Southey 2. 211-212).

6. Or at least a

more “authentic and ancient character of the Scottish ballad”: as many

scholars have noted, Scott took “liberties” with his various source materials,

constructing a single ballad from various old copies, adding words and even

whole stanzas, and often improving phraseology. As

Hughes notes in his “Prefatory Note,” Scott’s “aim was less to obtain an

accurate text than to stimulate an interest in the subject” (xvii).

said “I ought to apologise to you for having troubled you with anything of

my own when I had things like this for your ear.” “I felt at once,” says Ballantyne, “that his own verses were far above what Lewis

could ever do, and though, when I said this, he dissented, yet he seemed

pleased with the warmth of my approbation.” At parting, Scott threw out a

casual observation, that he wondered his old friend did not try to get some

little booksellers’ work, “to keep his types in play during the rest of the

week.” Ballantyne answered, that such an idea had not

before occurred to him—that he had no acquaintance with the

said “I ought to apologise to you for having troubled you with anything of

my own when I had things like this for your ear.” “I felt at once,” says Ballantyne, “that his own verses were far above what Lewis

could ever do, and though, when I said this, he dissented, yet he seemed

pleased with the warmth of my approbation.” At parting, Scott threw out a

casual observation, that he wondered his old friend did not try to get some

little booksellers’ work, “to keep his types in play during the rest of the

week.” Ballantyne answered, that such an idea had not

before occurred to him—that he had no acquaintance with the