|

|

Home | Corson Collection | Biography | Works | Image Collection | Recent Publications | Portraits | Correspondence | Forthcoming Events | Links | E-Texts | Contact The AbbotFirst Edition, First Impression: The Abbot. By the Author of "Waverley". In Three Volumes. Vol. I (II-III). Edinburgh: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, London; And for Archibald Constable and Co. And John Ballantyne, Edinburgh, 1820. Composition | Sources | Synopsis | Reception | Links Composition

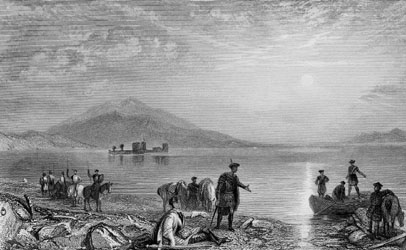

Scott's surviving correspondence suggests that he originally intended to deal with the dissolution of the monasteries and the imprisonment and escape of Queen Mary in the same novel. Scott did some preliminary work on The Monastery in August 1819 but only after the completion of Ivanhoe in the first week of November did he turn his full attention to the novel. As early as 8 November, however, he wrote to John Ballantyne to announce that The Monastery would run to four volumes or ('which is much better') be published in two parts comprised of three volumes each. Ballantyne subsequently proposed a sequel to the publisher Longmans in late December 1819, and the offer was promptly accepted. Scott's eagerness to publish the novel in two parts most likely stemmed from financial rather than aesthetic considerations. He stood in need of ready cash to meet expenses arising from his son's receipt of a military commission and from recent extensions to the Abbotsford estate. A second publisher's advance, duly received in January 1820, would provide a much-needed injection of capital. Throughout the negotiations for the sequel, the novel is referred to solely as the second 'part', 'branch', or 'class' of The Monastery. Only on 29 March do Constable's records first refer to The Abbot by its eventual title. Relatively little is known about the composition process of The Abbot, the surviving manuscript of which is incomplete. When The Monastery was published in March 1820, it seems likely that Scott did not immediately set to work on the sequel. According to a letter to Lady Abercorn, only half of the first volume was complete by 1 June. The intervening weeks had been hectic. Scott had travelled to London in March to receive his baronetcy, and had married his daughter Sophia to his future biographer John Gibson Lockhart on 29 April. The enforced break from writing had permitted Scott to gauge the largely negative public reaction to The Monastery and to re-organize his material so as to render The Abbot an autonomous narrative. In particular, he chose to abandon the White Lady, guardian spirit of the House of Avenel, who had displeased critics and readers alike. In the summer, Scott made rapid progress on the novel. The first two volumes were complete by 8 July, and the novel was advertised as due to be published in August. An overlong third volume occasioned a slight delay, and The Abbot finally appeared in Edinburgh on 2 September and in London on 4 September. As with The Monastery, publication was managed by Longmans of London, with Scott's usual publisher Constable temporarily relegated to the role of co-publisher. SourcesThe novel takes place between July 1567 and May 1568, spanning the imprisonment of Mary Queen of Scots at Lochleven, her enforced abdication, her escape from the Castle, defeat at Langside and subsequent flight to England. The events covered in the novel seal the triumph of the Protestant, pro-English party in England and ultimately pave the way to the Union of the English and Scottish Crowns under a Protestant monarch. Scott drew on the large collection of printed works relating to Mary that he had gathered at Abbotsford. Besides polemicists like the Protestants George Buchanan and John Knox and the Catholic John Leslie, Scott made use of eighteenth-century collections of original source material such as Samuel Jebb's De Vita & Rebus Gestis Serenissimae Principis Mariae Scotorum Reginae and Robert Keith's The History of the Affairs of the Church and State in Scotland. Scott also acknowledges his debt to George Chalmers's more recent Life of Mary, Queen of Scots, the publication of which in 1818 may have helped fix his interest on Mary's reign. Scott's hero, Roland Graeme, is a fictional character, but his theft of the keys of Lochleven Castle and liberation of the Queen are based on the actions of Willie Douglas, an orphan belonging to the Lochleven household, who remained a loyal servant of Mary until her death.

SynopsisThe orphaned hero, Roland Graeme, is brought up as a page by Lady Mary Avenel, heroine of The Monastery and now wife to Sir Halbert Glendinning. Although considered a penniless bastard, Roland becomes a favourite with his childless mistress until his impetuous character leads to his dismissal. Assisted by Sir Halbert, Roland enters the service of the Earl of Murray who, following the enforced abdication of Mary Queen of Scots, governs Scotland as Regent on behalf of the infant James VI. Murray appoints him as a page to the imprisoned Queen Mary and sends him to Lochleven Castle with instructions to act as a spy. However, Roland's sense of honour, his loyalty to Mary (instilled by his Catholic grandmother, Madgalen Graeme), and his love for Catherine Seyton, one of Mary Stuart's attendants, prevent him from acting out this role. In the end, Roland becomes instrumental in the queen's escape, remaining with her until she leaves Scotland. In this, he is assisted by the Abbot of Kennaquhair, Father Ambrosius (formerly Edward Glendinning), from whom the novel takes its title. Shortly before Mary's defeat at Langside, Roland discovers his true identity. He is not, as he thought, the illegitimate child of Catherine Graeme but the product of a legitimate marriage between Catherine and Julian Avenel, and thus heir to his benefactress's estates. Roland is pardoned by the Regent and marries Catherine Seyton.

ReceptionWith the publication of The Abbot, Scott regained the reputation he had established with Ivanhoe. The success of The Abbot was proof to him that the sixteenth century provided fertile ground for historical fiction and he would return to the period with his next novel Kenilworth. Lochleven Castle became a favourite destination for sightseers and the success of The Abbot prompted a revival of interest in (and partial reappraisal of) The Monastery. Reviews were largely favourable, with Blackwood's, the Literary Gazette, and the Quarterly Review being particularly enthusiastic. The Quarterly singled out Scott's skill in interweaving the loves of Catherine and Roland and the fate of Queen Mary: 'Never was a double plot better connected.' Reservations were expressed by the Edinburgh Review and Edinburgh Magazine. The former, while admiring the passages relating to Mary's escape and the battle of Langside, did not approve of the title of the novel, arguing that the Abbot played only a minor part, and described Catherine Seyton as a 'wilful deterioration of Diana Vernon'. The latter protested against the levity of Queen Mary and the coarseness of her language, arguing that both were unhistorical. LinksLast updated: 19-Dec-2011 |

|

Along amongst the Waverley Novels, The Abbot was explicitly

presented as the sequel to an earlier volume. The Introductory

Epistle to the First Edition informs the reader that the narrative

is the continuation of the Benedictine manuscript from which Scott

purported

to have

drawn his preceding novel

Along amongst the Waverley Novels, The Abbot was explicitly

presented as the sequel to an earlier volume. The Introductory

Epistle to the First Edition informs the reader that the narrative

is the continuation of the Benedictine manuscript from which Scott

purported

to have

drawn his preceding novel