|

|

Home

| Corson Collection | Biography

| Works | Image

Collection | Recent Publications

| Portraits | Correspondence

| Forthcoming Events |

Links | E-Texts |

Contact

The Ballantyne Brothers

|

Scott first met James Ballantyne (1772-1833) when

attending Kelso Grammar School in 1783 (see School

and University). The oldest son of a thriving local merchant,

he shared Scott's love of literature, and the two rapidly became

good friends. Like Scott, James went on to study Law at Edinburgh

University, returning to Kelso in 1795 to set up in practice

as a solicitor. The following year he launched the staunchly

pro-Tory newspaper the Kelso Mail, which he both edited

and printed. |

In 1799, James privately printed the two pamphlets with which

Scott began his writing career: An Apology for Tales of Terror

(containing ballads and translations intended for publication in

Matthew Gregory

Lewis's much-delayed anthology Tales of Wonder)

and the ballad 'The

Eve of St. John' (see Literary Beginnings).

Thus began a literary and business partnership that would last

Scott's

lifetime. Scott was so pleased with the typographical excellence

of these two slim volumes that he offered James the opportunity

of printing the collection of Border ballads that he was in the

process of gathering. When these eventually appeared as the two

large octavo volumes of Minstrelsy

of the Scottish Border (1802), there was general astonishment

in the British book-trade that a small-town printer could produce

work of such quality. Scott immediately urged his friend to relocate

to Edinburgh, but James wished first to train up the younger

of

his two brothers, Alexander ('Sandy'), to take over the running

of the Kelso Mail. Sandy, father of the Victorian children's

writer, R.M. Ballantyne, would eventually buy James's entire

interest

in the Kelso Mail in 1806.

|

|

Click on the thumbnail to view a full-size

facsimile of the front page of the first issue of the Kelso

Mail (April 13, 1797). The March 1798 issue of the Kelso

Mail contained 'The Erl-King', Scott's translation of

a Goethe ballad.

|

Scott finally persuaded James to move to Edinburgh in 1803, loaning

him £500 to increase the liquid capital of his business. James

initially set up his presses in two small rooms in Holyrood House,

but thriving business soon led him to seek larger premises. Orders

flooded in from Edinburgh publishers and Scott was instrumental

in securing for Ballantyne the right to print Session papers (see

Professional Life). James first moved to

Foulis Close in the Canongate then, in 1805, to Paul's Work, situated

between the Canongate and Leith Wynd.

|

Click on the thumbnail to see a full-scale reproduction

of a sepia drawing of James Ballantyne & Co's Printing Office

at Paul's Work by an unknown artist. |

In that same year, though, the unprecedented success of The

Lay of the Last Minstrel,

printed by Ballantyne for Archibald Constable, severely strained

the small firm's financial resources. Printing jobs for other publishers

were delayed for want of capital to purchase materials (paper, inks,

type-faces, extra presses). Customers habitually demanded generous

credit before placing orders so money was slow coming in. However

prosperous the business appeared, Ballantyne sometimes lacked the

ready funds to pay his employees' wages. He thus requested a further

loan from Scott. Scott had recently been left £5,000 on the

death of his uncle, Robert Scott, and grasped the opportunity to

obtain a share in a business with excellent long-term prospects.

He offered to inject further capital on condition of being made

a partner. An agreement was signed on May 26, 1805, whereby Scott

advanced a further £1,500 (his original £500 loan being

converted into share capital) and became owner of a third of the

company's stock. The arrangement was kept a close secret from all

but Scott's friend Will Erskine.

With

the aid of Scott's capital the press continued to prosper. Scott

threw himself into a great deal of editorial work on scholarly and

antiquarian volumes which he insisted must be printed by James Ballantyne

and Co. Scott's achievements as an editor are perhaps the most overlooked

aspect of his literary career. Most significant in these years was

the eighteen-volume set of the works of John Dryden (portrayed,

left) who many critics have seen as Scott's role model as a professional

writer. Other works edited or part-edited by Scott include Memoirs

of Captain George Carleton, Memoirs of Robert Carey,

State Papers and Letters of Sir Ralph Sadler, and Joseph

Strutt's Queenhoo-Hall (see Scott the

Novelist). These all brought considerable profits to Ballantyne

and Co. (and, by extension to Scott himself) but little for the

publishers involved. With

the aid of Scott's capital the press continued to prosper. Scott

threw himself into a great deal of editorial work on scholarly and

antiquarian volumes which he insisted must be printed by James Ballantyne

and Co. Scott's achievements as an editor are perhaps the most overlooked

aspect of his literary career. Most significant in these years was

the eighteen-volume set of the works of John Dryden (portrayed,

left) who many critics have seen as Scott's role model as a professional

writer. Other works edited or part-edited by Scott include Memoirs

of Captain George Carleton, Memoirs of Robert Carey,

State Papers and Letters of Sir Ralph Sadler, and Joseph

Strutt's Queenhoo-Hall (see Scott the

Novelist). These all brought considerable profits to Ballantyne

and Co. (and, by extension to Scott himself) but little for the

publishers involved.

The

press's greatest success in these years, however, was Scott's second

narrative poem Marmion

(1808) which proved even more popular than The Lay of the Last

Minstrel. Marmion was printed by Ballantyne for the publisher

Archibald Constable (portrayed, right) but Scott was now keen to

distance himself from Constable. He detested the Whig politics of

Constable's Edinburgh Review and had been particularly incensed

by Francis Jeffrey's condemnation of British intervention in the

Peninsular War which had appeared on its pages. He had also been

hurt by Jeffrey's high-handed critique of Marmion. Keen to

partake of the huge profits with which he was currently lining Constable's

pockets, Scott decided to set up a rival publishing house. Looking

around for a capable manager, his choice fell on the middle Ballantyne

brother, John. The

press's greatest success in these years, however, was Scott's second

narrative poem Marmion

(1808) which proved even more popular than The Lay of the Last

Minstrel. Marmion was printed by Ballantyne for the publisher

Archibald Constable (portrayed, right) but Scott was now keen to

distance himself from Constable. He detested the Whig politics of

Constable's Edinburgh Review and had been particularly incensed

by Francis Jeffrey's condemnation of British intervention in the

Peninsular War which had appeared on its pages. He had also been

hurt by Jeffrey's high-handed critique of Marmion. Keen to

partake of the huge profits with which he was currently lining Constable's

pockets, Scott decided to set up a rival publishing house. Looking

around for a capable manager, his choice fell on the middle Ballantyne

brother, John.

On

the face of it, John Ballantyne (1774-1821), with his hard-won reputation

as the black sheep of the family, was a perverse choice. After serving

an apprenticeship at a London banking house, he had been taken on

as a partner in his father's business in Kelso. In 1797, however,

the two men quarreled bitterly over John's choice of bride, and

John set up a rival store. Although it initially prospered, mismanagement,

womanizing and all-round high living brought John near ruin by 1806.

With difficulty, James dissuaded him from emigrating to the West

Indies and offered him a clerical post in his printing office, provided

that he mend his ways and make up with his now estranged wife. In

this new capacity John impressed Scott with his inventive approach

to book-keeping. Rapidly tiring of office drudgery, he leapt at

the chance to head the publishing firm which was founded in 1809.

Based in Hanover Street, it would trade under the name of John Ballantyne

and Co. Scott acquired a half-share in the business (again a closely

guarded secret), and James and John were allotted a quarter share

each. Profits were to be divided in the same proportion and matters

of policy to be decided jointly. Later in 1809 Scott renegotiated

his position with James Ballantyne's printing company, obtaining

a half-share in the business through a new injection of capital. On

the face of it, John Ballantyne (1774-1821), with his hard-won reputation

as the black sheep of the family, was a perverse choice. After serving

an apprenticeship at a London banking house, he had been taken on

as a partner in his father's business in Kelso. In 1797, however,

the two men quarreled bitterly over John's choice of bride, and

John set up a rival store. Although it initially prospered, mismanagement,

womanizing and all-round high living brought John near ruin by 1806.

With difficulty, James dissuaded him from emigrating to the West

Indies and offered him a clerical post in his printing office, provided

that he mend his ways and make up with his now estranged wife. In

this new capacity John impressed Scott with his inventive approach

to book-keeping. Rapidly tiring of office drudgery, he leapt at

the chance to head the publishing firm which was founded in 1809.

Based in Hanover Street, it would trade under the name of John Ballantyne

and Co. Scott acquired a half-share in the business (again a closely

guarded secret), and James and John were allotted a quarter share

each. Profits were to be divided in the same proportion and matters

of policy to be decided jointly. Later in 1809 Scott renegotiated

his position with James Ballantyne's printing company, obtaining

a half-share in the business through a new injection of capital.

John Ballantyne and Co.'s first publication, Scott's The

Lady of the Lake appeared in 1810. The huge profits led

the three partners into a wildly optimistic estimate of their future

prospects. The selection of future titles for publication fell to

Scott himself, who launched a series of commercially disastrous

titles. Profits from The Lady of the Lake were not ploughed

back into the business, and debts mounted rapidly. It was at this

juncture that Scott decided to throw further capital into the purchase

of Cartley Hole Farm, soon to be renamed Abbotsford.

Half of this sum was raised by John Ballantyne on the security of

the as yet unwritten Rokeby,

the poem to which Scott was looking both to cover his building expenses

and to bale out the publishing house.

By

spring 1813, a series of banking crises had brought the war-ravaged

economy to a crisis. John Ballantyne and Co. had been forced to

sell some of the copyrights of Scott's works (their most valuable

assets) to raise ready capital. Rokeby, although a great

success by any other poet's standards, fell far short of being the

panacea to all the company's ills. The Ballantynes reluctantly approached

Archibald Constable who offered £1,300 for part of their unsold

stock, on condition that the firm wind up immediately and Scott

allow him to purchase a quarter share of the copyright of Rokeby

for an extra £700. Constable also agreed to prepare a report

into the financial state of both the printing and publishing companies,

concluding that they must raise £4,000 immediately to avoid

bankruptcy. Bankruptcy would have made public the secret arrangement

whereby Scott profited from the printing, publishing, and royalties

of every book he wrote. He would have been forced to resign as Clerk

to the Court of Session and thus lose his regular income. In desperation,

Scott turned to his patron, the Duke of Buccleuch (portrayed, above

right), who agreed to stand guarantor behind a redeemable annuity

for a sum of £4,000 (see Financial

Hardship). By

spring 1813, a series of banking crises had brought the war-ravaged

economy to a crisis. John Ballantyne and Co. had been forced to

sell some of the copyrights of Scott's works (their most valuable

assets) to raise ready capital. Rokeby, although a great

success by any other poet's standards, fell far short of being the

panacea to all the company's ills. The Ballantynes reluctantly approached

Archibald Constable who offered £1,300 for part of their unsold

stock, on condition that the firm wind up immediately and Scott

allow him to purchase a quarter share of the copyright of Rokeby

for an extra £700. Constable also agreed to prepare a report

into the financial state of both the printing and publishing companies,

concluding that they must raise £4,000 immediately to avoid

bankruptcy. Bankruptcy would have made public the secret arrangement

whereby Scott profited from the printing, publishing, and royalties

of every book he wrote. He would have been forced to resign as Clerk

to the Court of Session and thus lose his regular income. In desperation,

Scott turned to his patron, the Duke of Buccleuch (portrayed, above

right), who agreed to stand guarantor behind a redeemable annuity

for a sum of £4,000 (see Financial

Hardship).

Constable was to publish Scott next narrative poem The

Lord of the Isles and the first three Waverley Novels (Waverley,

Guy Mannering,

and The Antiquary).

After publishing the First Series of Tales of My Landlord

(The Black Dwarf and

Old Mortality)

with William Blackwood, Scott returned to Constable for Rob

Roy (1817), eventually persuading him to buy all of John

Ballantyne and Co.'s unsold stock. The contract for each new novel

stipulated that that the printing be undertaken by James Ballantyne

and Co. and that Constable had the right only to manage and sell

an agreed number of copies. In effect, then, Scott and James Ballantyne

controlled production.

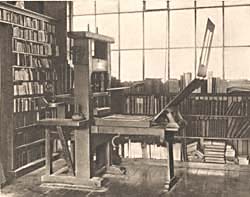

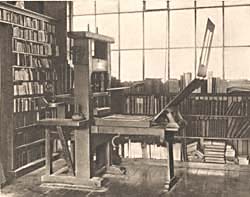

James's role extended far beyond that of business partner or printer.

His and Scott's was a unique literary relationship. Scott consulted

James on the artistic merit and likely commercial success of each

work. James read Scott's proofs, acting as editor rather than mere

proof-reader. He would point out inconsistencies in detail and gaps

in the text, insert names of speakers in dialogue, correct punctuation

and grammatical errors, and remove close verbal repetitions. The

annotated proofs were then sent back to Scott who made further alterations.

James made further editorial interventions on post-authorial proofs,

making changes that were probably never inspected by Scott. (Portrayed,

above left, is a wooden press used in printing the Waverley Novels

at the Ballantyne Press.)

James's role extended far beyond that of business partner or printer.

His and Scott's was a unique literary relationship. Scott consulted

James on the artistic merit and likely commercial success of each

work. James read Scott's proofs, acting as editor rather than mere

proof-reader. He would point out inconsistencies in detail and gaps

in the text, insert names of speakers in dialogue, correct punctuation

and grammatical errors, and remove close verbal repetitions. The

annotated proofs were then sent back to Scott who made further alterations.

James made further editorial interventions on post-authorial proofs,

making changes that were probably never inspected by Scott. (Portrayed,

above left, is a wooden press used in printing the Waverley Novels

at the Ballantyne Press.)

In autumn 1815 James proposed marriage to Christina Hogarth. Her

father would only consent if James could prove himself free from

debt. Scott agreed to discharge James from his liabilities for the

publishing house's debts on condition that Scott assume ownership

of James Ballantyne and Co., retaining James as a salaried manager.

The irrepressible John, meanwhile, had reinvented himself as a successful

auctioneer in his publishing house's old premises. He had even succeeded

in selling off a good deal of his own stock by putting it in other

people's sale catalogues. Esteeming his ability to drive a hard

bargain and his skill in confidential bill discounting, money-changing,

loan raising, and double accountancy, Scott continued to employ

him as his literary agent.

| As a theatre critic for the Edinburgh Evening

Courant, and patron of music and the arts, James soon acquired

a circle of like-minded friends. His rooms in St. John Street

near Paul's Work (portrayed, right) became a meeting place for

literary, theatrical, and concert-hall personalities. (Click here for a page, with photograph, on the history of St. John Street, published by Moray House School of Education.) Nonetheless

his financial circumstances remained straitened. He was constantly

under pressure to renew or pay back loans contracted in the

early days of Ballantyne Press. He had been forced to borrow

heavily in order to keep his capital in the enterprise on a

par with Scott's, and later in order to invest in John Ballantyne

and Co. |

|

James's financial worries eased when, in 1817, he purchased the

Edinburgh Weekly Journal along with his brother-in-law George

Hogarth. James assumed editorship and employed John as a musical

and drama critic, in which capacity he soon gained a considerable

reputation. Circulation rapidly expanded, and Hogarth ensured that

profits were ploughed back into the business. By now, however, John's

decades of hard living were catching up with him. After several

years of ill health, he died on June 16, 1821 of pulmonary consumption.

Shortly before his death, Scott had offered to write biographical

introductions for a project that John had long cherished: a series

of reprints of popular novels and romances at readily affordable

prices. Scott saw through the publication of 'Ballantyne's Novelists'

Library' in memory of his dead friend.

Scott

now promoted James Ballantyne from manager of the printing business

to personal agent and partner, while Sandy Ballantyne took over

the editorship of the Weekly Journal. The Ballantyne Press

was massively in demand, printing works for publishing houses both

north and south of the Border, and cornering the market for printing

legal stationary and official documents thanks to Scott's influence.

But money that should have gone on repaying loans had gone instead

to pay for work on Abbotsford. Ballantyne was quite aware that Scott

had run up vast debts in the company's name but assumed that the

land and buildings of Abbotsford were the firm's security. Unknown

to James, though, Scott settled the whole estate on his newly married

son, Walter (portrayed, above left) in 1825, thus putting it beyond

the reach of creditors. Scott

now promoted James Ballantyne from manager of the printing business

to personal agent and partner, while Sandy Ballantyne took over

the editorship of the Weekly Journal. The Ballantyne Press

was massively in demand, printing works for publishing houses both

north and south of the Border, and cornering the market for printing

legal stationary and official documents thanks to Scott's influence.

But money that should have gone on repaying loans had gone instead

to pay for work on Abbotsford. Ballantyne was quite aware that Scott

had run up vast debts in the company's name but assumed that the

land and buildings of Abbotsford were the firm's security. Unknown

to James, though, Scott settled the whole estate on his newly married

son, Walter (portrayed, above left) in 1825, thus putting it beyond

the reach of creditors.

Thus in the financial crisis of 1826, when the failure of Hurst,

Robinson & Company brought in its wake that of Archibald Constable

and the Ballantyne Press (see Financial Hardship).

James found himself liable for half of the company's debts. He was

forced to sell his new home and all the family valuables but permitted

to continue living at St. John Street. Under the surveillance of

the trust appointed to administer Scott's earnings, James was permitted

to stay on as manager of the printing business. A salary of £400

p.a. with no benefits meant a steep decline in his standard of living.

Sandy Ballantyne, who had invested all his own spare capital in

the Ballantyne Press, was permitted to resume management of the

Edinburgh Weekly Journal.

The fortunes of the surviving Ballantyne brothers gradually revived.

Many Edinburgh businessmen felt that James bore little guilt in

the collapse of his firm, pointing instead to Scott's incessant

demand for funds. Soon, Alexander Cowan, chairman of Scott's trustees,

was sufficiently confident to buy the printing house as a going

concern for £10,000 in Ballantyne's name. James contracted

to repay him the capital sum with interest over the coming years.

Shortly afterwards Sandy was admitted into partnership. The firm

gradually improved its turnover, and the loan was repaid by the

end of 1832.

| Although Scott had no official business relationship with

James Ballantyne & Co. after 1826, loyalty led him to insist

that his new publisher Robert Cadell (portrayed, right) continue

to use the press. It appears that in the final years of Scott's

life, relations with James began to cool. Scott was hurt by

his adverse criticism of Anne

of Geierstein and Count

Robert of Paris and appalled by his conversion to Whig

politics and evangelical religion. Cadell, who had little time

for the Ballantynes and thought their typographical prowess

overrated, sought to prise them further apart by using James

to convey his own reservations about Scott's later works. |

|

James, who had been devastated by the loss of his wife in 1829,

died shortly after Scott on January 26, 1833. His son, John Alexander

Ballantyne, took over management of the Ballantyne Press with the

help of John Hughes (who had risen up from the post of compositor).

Business continued to thrive for a few years but by mid-century

they were suffering serious competition from other steam presses.

In Edinburgh, Blackwood's had emerged as serious rivals, and the

publishing world was increasingly centred on London. Their Edinburgh

printing works finally closed in 1916.

For further information on the Ballantyne brothers, consult the

following works in addition to those cited on the Bibliography

page:

- The Ballantyne Press and Its Founders, 1796-1908 (Edinburgh:

Ballantyne, Hanson & Co., 1909)

- The History of the Ballantyne Press and Its Connection with

Sir Walter Scott, Bart. (Edinburgh: Ballantyne Press, 1871)

- Quayle, Eric, Ballantyne the Brave: A Victorian Writer and

His Family (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1967)

Back to Biography Index

Last updated: 11-Dec-2007

© Edinburgh University Library

|

|

With

the aid of Scott's capital the press continued to prosper. Scott

threw himself into a great deal of editorial work on scholarly and

antiquarian volumes which he insisted must be printed by James Ballantyne

and Co. Scott's achievements as an editor are perhaps the most overlooked

aspect of his literary career. Most significant in these years was

the eighteen-volume set of the works of John Dryden (portrayed,

left) who many critics have seen as Scott's role model as a professional

writer. Other works edited or part-edited by Scott include Memoirs

of Captain George Carleton, Memoirs of Robert Carey,

State Papers and Letters of Sir Ralph Sadler, and Joseph

Strutt's Queenhoo-Hall (see

With

the aid of Scott's capital the press continued to prosper. Scott

threw himself into a great deal of editorial work on scholarly and

antiquarian volumes which he insisted must be printed by James Ballantyne

and Co. Scott's achievements as an editor are perhaps the most overlooked

aspect of his literary career. Most significant in these years was

the eighteen-volume set of the works of John Dryden (portrayed,

left) who many critics have seen as Scott's role model as a professional

writer. Other works edited or part-edited by Scott include Memoirs

of Captain George Carleton, Memoirs of Robert Carey,

State Papers and Letters of Sir Ralph Sadler, and Joseph

Strutt's Queenhoo-Hall (see  The

press's greatest success in these years, however, was Scott's second

narrative poem

The

press's greatest success in these years, however, was Scott's second

narrative poem  On

the face of it, John Ballantyne (1774-1821), with his hard-won reputation

as the black sheep of the family, was a perverse choice. After serving

an apprenticeship at a London banking house, he had been taken on

as a partner in his father's business in Kelso. In 1797, however,

the two men quarreled bitterly over John's choice of bride, and

John set up a rival store. Although it initially prospered, mismanagement,

womanizing and all-round high living brought John near ruin by 1806.

With difficulty, James dissuaded him from emigrating to the West

Indies and offered him a clerical post in his printing office, provided

that he mend his ways and make up with his now estranged wife. In

this new capacity John impressed Scott with his inventive approach

to book-keeping. Rapidly tiring of office drudgery, he leapt at

the chance to head the publishing firm which was founded in 1809.

Based in Hanover Street, it would trade under the name of John Ballantyne

and Co. Scott acquired a half-share in the business (again a closely

guarded secret), and James and John were allotted a quarter share

each. Profits were to be divided in the same proportion and matters

of policy to be decided jointly. Later in 1809 Scott renegotiated

his position with James Ballantyne's printing company, obtaining

a half-share in the business through a new injection of capital.

On

the face of it, John Ballantyne (1774-1821), with his hard-won reputation

as the black sheep of the family, was a perverse choice. After serving

an apprenticeship at a London banking house, he had been taken on

as a partner in his father's business in Kelso. In 1797, however,

the two men quarreled bitterly over John's choice of bride, and

John set up a rival store. Although it initially prospered, mismanagement,

womanizing and all-round high living brought John near ruin by 1806.

With difficulty, James dissuaded him from emigrating to the West

Indies and offered him a clerical post in his printing office, provided

that he mend his ways and make up with his now estranged wife. In

this new capacity John impressed Scott with his inventive approach

to book-keeping. Rapidly tiring of office drudgery, he leapt at

the chance to head the publishing firm which was founded in 1809.

Based in Hanover Street, it would trade under the name of John Ballantyne

and Co. Scott acquired a half-share in the business (again a closely

guarded secret), and James and John were allotted a quarter share

each. Profits were to be divided in the same proportion and matters

of policy to be decided jointly. Later in 1809 Scott renegotiated

his position with James Ballantyne's printing company, obtaining

a half-share in the business through a new injection of capital. By

spring 1813, a series of banking crises had brought the war-ravaged

economy to a crisis. John Ballantyne and Co. had been forced to

sell some of the copyrights of Scott's works (their most valuable

assets) to raise ready capital. Rokeby, although a great

success by any other poet's standards, fell far short of being the

panacea to all the company's ills. The Ballantynes reluctantly approached

Archibald Constable who offered £1,300 for part of their unsold

stock, on condition that the firm wind up immediately and Scott

allow him to purchase a quarter share of the copyright of Rokeby

for an extra £700. Constable also agreed to prepare a report

into the financial state of both the printing and publishing companies,

concluding that they must raise £4,000 immediately to avoid

bankruptcy. Bankruptcy would have made public the secret arrangement

whereby Scott profited from the printing, publishing, and royalties

of every book he wrote. He would have been forced to resign as Clerk

to the Court of Session and thus lose his regular income. In desperation,

Scott turned to his patron, the Duke of Buccleuch (portrayed, above

right), who agreed to stand guarantor behind a redeemable annuity

for a sum of £4,000 (see

By

spring 1813, a series of banking crises had brought the war-ravaged

economy to a crisis. John Ballantyne and Co. had been forced to

sell some of the copyrights of Scott's works (their most valuable

assets) to raise ready capital. Rokeby, although a great

success by any other poet's standards, fell far short of being the

panacea to all the company's ills. The Ballantynes reluctantly approached

Archibald Constable who offered £1,300 for part of their unsold

stock, on condition that the firm wind up immediately and Scott

allow him to purchase a quarter share of the copyright of Rokeby

for an extra £700. Constable also agreed to prepare a report

into the financial state of both the printing and publishing companies,

concluding that they must raise £4,000 immediately to avoid

bankruptcy. Bankruptcy would have made public the secret arrangement

whereby Scott profited from the printing, publishing, and royalties

of every book he wrote. He would have been forced to resign as Clerk

to the Court of Session and thus lose his regular income. In desperation,

Scott turned to his patron, the Duke of Buccleuch (portrayed, above

right), who agreed to stand guarantor behind a redeemable annuity

for a sum of £4,000 (see  James's role extended far beyond that of business partner or printer.

His and Scott's was a unique literary relationship. Scott consulted

James on the artistic merit and likely commercial success of each

work. James read Scott's proofs, acting as editor rather than mere

proof-reader. He would point out inconsistencies in detail and gaps

in the text, insert names of speakers in dialogue, correct punctuation

and grammatical errors, and remove close verbal repetitions. The

annotated proofs were then sent back to Scott who made further alterations.

James made further editorial interventions on post-authorial proofs,

making changes that were probably never inspected by Scott. (Portrayed,

above left, is a wooden press used in printing the Waverley Novels

at the Ballantyne Press.)

James's role extended far beyond that of business partner or printer.

His and Scott's was a unique literary relationship. Scott consulted

James on the artistic merit and likely commercial success of each

work. James read Scott's proofs, acting as editor rather than mere

proof-reader. He would point out inconsistencies in detail and gaps

in the text, insert names of speakers in dialogue, correct punctuation

and grammatical errors, and remove close verbal repetitions. The

annotated proofs were then sent back to Scott who made further alterations.

James made further editorial interventions on post-authorial proofs,

making changes that were probably never inspected by Scott. (Portrayed,

above left, is a wooden press used in printing the Waverley Novels

at the Ballantyne Press.)

Scott

now promoted James Ballantyne from manager of the printing business

to personal agent and partner, while Sandy Ballantyne took over

the editorship of the Weekly Journal. The Ballantyne Press

was massively in demand, printing works for publishing houses both

north and south of the Border, and cornering the market for printing

legal stationary and official documents thanks to Scott's influence.

But money that should have gone on repaying loans had gone instead

to pay for work on Abbotsford. Ballantyne was quite aware that Scott

had run up vast debts in the company's name but assumed that the

land and buildings of Abbotsford were the firm's security. Unknown

to James, though, Scott settled the whole estate on his newly married

son, Walter (portrayed, above left) in 1825, thus putting it beyond

the reach of creditors.

Scott

now promoted James Ballantyne from manager of the printing business

to personal agent and partner, while Sandy Ballantyne took over

the editorship of the Weekly Journal. The Ballantyne Press

was massively in demand, printing works for publishing houses both

north and south of the Border, and cornering the market for printing

legal stationary and official documents thanks to Scott's influence.

But money that should have gone on repaying loans had gone instead

to pay for work on Abbotsford. Ballantyne was quite aware that Scott

had run up vast debts in the company's name but assumed that the

land and buildings of Abbotsford were the firm's security. Unknown

to James, though, Scott settled the whole estate on his newly married

son, Walter (portrayed, above left) in 1825, thus putting it beyond

the reach of creditors.