|

|

Home | Corson Collection | Biography | Works | Image Collection | Recent Publications | Portraits | Correspondence | Forthcoming Events | Links | E-Texts | Contact WaverleyFirst Edition, First Impression: Waverley; or 'Tis Sixty Years Since. In Three Volumes. Edinburgh: Printed by James Ballantyne and Co. For Archibald Constable and Co. Edinburgh; And Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, London,1814. Composition | Synopsis | Reception | Links Composition

Recent scholars have queried Scott's chronology in light of strong textual and circumstantial evidence that Scott was actively engaged with the novel over the period 1808-10. For Claire Lamont (1981) and Jane Millgate (1984), this consitutes an intermediate phase between the two stages posited by Scott (1805 and 1813-14) (see Bibliography). Peter D. Garside (1986), however, finds little compelling evidence that the novel was begun c1805 and is inclined to bring forward its genesis to the 1808-10 period. He notes that Longmans advertised the novel as a forthcoming publication as early as August 1810. There are similarities both in the paper used and in the narrative content between the opening chapters of Waverley and Scott's Ashestiel Memoirs (1808-11). There are also close textual and thematic parallels with The Lady of the Lake (1810). Garside observes that the fashionable modes of fiction parodied in Chapter I of Waverley -- novels of scandal and sentiment -- were at their height between 1807 and 1810 but fit ill with an 1805 genesis. The prevailing literary climate would also have appeared more favourable to an experiment with a tale of national or regional manners following the success of Maria Edgeworth's Tales of Fashionable Life (1809), Elizabeth Hamilton's Cottagers of Glenburnie (1808), and, in particular, Jane Porter's The Scottish Chiefs (1810). 1810, finally, was the date of a trip to the Highlands and Western Isles, described in Scott's Letters in terms reminiscent of the early Highland scenes of Waverley. In Garside's hypothesis, much of the first volume of Waverley was complete by 1810. Work on the novel was suspended by the time-consuming and expensive move to Abbotsford in 1811. The consequent need to raise ready cash led Scott to return to the more lucrative poetry market with Rokeby (1813). It was the relative failure of Rokeby that led Scott to resume work on Waverley in late 1813. |

|||

|

|

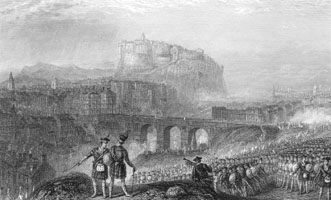

Click on the thumbnail to view the full-size image of Fergus MacIvor introducing Waverley to Bonnie Prince Charlie. This engraving by Lumb Stocks after a painting by John Blake MacDonald was published in Eight Engravings in Illustration of 'Waverley' for the Members of the Royal Association for the Promotion of the Fine Arts in Scotland (Edinburgh: The Association, 1865). |

|||

Conversely, there seems little reason to question Lockhart's claim that the first volume was completed over the Christmas vacation of 1813-14. In order to preserve his anonymity, Scott asked John Ballantyne to copy the manuscript out in his own hand before sending the first volume to press. Once printed, John Ballantyne showed it to Archibald Constable who immediately recognized that the work was Scott's and offered the exceptional sum of £700 for the copyright. Scott replied that the sum was excessive should the novel fail and inadequate should it succeed. It was resolved that publisher and author should share the profits equally, a settlement that Constable would come to regret. Work on Waverley was delayed by Scott's efforts to resolve his financial affairs (see Financial hardship), by negotiations with Constable over Scott's last major poetic work The Lord of the Isles, and by work on Abbotsford. Settling down to complete the novel in June 1814, Scott wrote the second and third volumes in an extraordinary three-week burst. Completed on 1 July, Waverley was rushed through the press and published on 7 July, a few weeks before Scott's 43rd birthday. Once again, the manuscript had been copied out in John Ballantyne's hand to preserve Scott's incognito, and the novel was published anonymously with only Scott's closeset associates being let into the secret. (For the factors that may have led Scott to preserve his anonymity, see Scott the Novelist).

SynopsisWaverley is set during the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745, which sought to restore the Stuart dynasty in the person of Charles Edward Stuart (or 'Bonnie Prince Charlie'). The hero is a young Englishman, Edward Waverley. Neglected by his pro-Hanoverian father, Edward is brought up by his elderly uncle, the Jacobite-leaning Sir Everard Waverley. Like Scott himself, Edward reads widely in poetry and romance as a child, creating an imaginary world that he much prefers to a lacklustre present. Having obtained a commission in the army, he is sent to Scotland in 1745. During a spell of leave, he visits his uncle's friend and fellow Jacobite, the Baron of Bradwardine at Tully-Veolan, forming an attachment to his daughter Rose. A spirit of adventure now leads him to visit the lair of Donald Bean Lean, a Highland freebooter, and the great hall at Glennaquoich, home to Fergus MacIvor, a young Highland chieftain and ardent Jacobite. Here Edward witnesses a patriarchal society where chieftain and follower feast together united by ties of kinship. Edward's romantic sensibilities are deeply affected by their fanatical enthusiasm for the Jacobite cause, particularly when embodied in Fergus's beautiful sister Flora. The frequentation of known Jacobites compromises Edward with his regiment, leading ultimately to his dismissal and arrest. Rescued by Rose, Edward joins the Jacobite forces even though reason tells him that Charles Edward Stuart's attempt to capture the British throne is doomed to failure. He is captivated by the personal charm of the Prince, impressed by Flora's devotion, and coerced by the powerful personality of Fergus MacIvor. However, when the Jacobite cause fails, Waverley is forced into hiding and is only freed when General Talbot, whose life he has saved at the Battle of Prestonpans, grants him a pardon. After attending the trial and condemnation of Fergus, Edward is decisively rejected by Flora. He then marries the placid Rose Bradwardine, who represents the rational, realistic present of post-Union Scotland as opposed to the colourful, passionate past personified by Flora. ReceptionThe success of Waverley was phenomenal and established Scott as a novelist with an international reputation. The first edition of one thousand copies sold out within two days of publication, and by November a fourth edition was at the presses. The critics too were almost unanimously enthusiastic. The fullest and most perceptive analysis was provided by Francis Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review. In Jeffrey's view, Waverley cast 'the whole tribe of ordinary novels into the shade'. The secret of the author's success lay in his truth to nature 'even in the most marvellous parts of his story'. Such were his powers of observation and fidelity to 'actual experience' that the reader saw in the novel 'an instructive exposition of human actions and energies' rather than 'a bewildering series of dreams and exaggerations'. Waverley's faults, deriving from a creaking, hastily constructed plot, were redeemed by the force of its characterization and vividness of its descriptive passages. Other journals echoed Jeffrey's praise, further complimenting the author on his easy flowing style and knowledge of the past. Only one reviewer, John Wilson Croker for the Quarterly Review, expressed substantial reservations, objecting to the obscurity of the Scots dialogue, historical inaccuracies, and the very mixture of history and 'romance'. Despite Scott's efforts to preserve his anonymity, almost every reviewer guessed that Waverley was his work. Many readers too recognized his hand. One, Jane Austen, wrote: 'Walter Scott has no business to write novels, especially good ones. -- It is not fair. He has Fame and Profit enough as a Poet, and should not be taking the bread out of other people's mouths.-- I do not like him, and do not mean to like Waverley if I can help it -- but fear I must' (letter to Anna Austen of 28 September 1814).

LinksLast updated: 19-Dec-2011 |

||||

Scott's own account of the composition of Waverley is

well-known but has been increasingly questioned in recent scholarship.

According to the General Preface (1829) to the 'Magnum Opus' edition

of the Waverley Novels, he began work on the novel 'about the year

1805'. Inspired by tales that he had heard from veterans of the

'45 and by his own youthful travels in the Highlands, he saw the

fictional potential of a clash of cultures, he felt sure that 'the

ancient traditions and high spirit of a people who, living in a

civilized age and country, retained so strong a tincture of manners

belonging to an early period of society must afford a subject favorable

for romance'. Having written some seven chapters, he asked his

friend William Erskine for his opinion. This being unfavourable,

Scott was reluctant to risk his reputation as poet by proceeding

any further, and set the manuscript aside. In September 1810 he

turned to

Scott's own account of the composition of Waverley is

well-known but has been increasingly questioned in recent scholarship.

According to the General Preface (1829) to the 'Magnum Opus' edition

of the Waverley Novels, he began work on the novel 'about the year

1805'. Inspired by tales that he had heard from veterans of the

'45 and by his own youthful travels in the Highlands, he saw the

fictional potential of a clash of cultures, he felt sure that 'the

ancient traditions and high spirit of a people who, living in a

civilized age and country, retained so strong a tincture of manners

belonging to an early period of society must afford a subject favorable

for romance'. Having written some seven chapters, he asked his

friend William Erskine for his opinion. This being unfavourable,

Scott was reluctant to risk his reputation as poet by proceeding

any further, and set the manuscript aside. In September 1810 he

turned to