|

|

Home | Corson

Collection | Biography | Works | Image

Collection | Recent Publications | Portraits | Correspondence | Forthcoming

Events | Links | E-Texts | Contact

Scott the Novelist

Early Experiments

in Fiction

Scott had been an enthusiastic novel-reader since his school years

and had acquired not only an exhaustive knowledge of the English

novel tradition but extensive familiarity with the classics of

French, German, and Spanish fiction (see School

and University and Literary Beginnings).

According to his own account in the 'General Preface' to the 'Magnum

Opus' edition of the Waverley Novels (1829), Scott's first experiments

with prose fiction date from the turn of the nineteenth century.

Two fragments survive (published as appendices to the 'General

Preface'). Thomas the Rhymer was destined to be a 'tale

of chivalry' in the style of Horace Walpole's The Castle of

Otranto, 'with plenty of Border characters, and supernatural

incident'. The Lord of Ennerdale too was strongly influenced

by prevailing Gothic models such as Walpole, Anne Radcliffe, and

'Monk' Lewis. Neither work was carried beyond its first chapter.

Scott

did not, though, abandon the ambition to write prose fiction. According

to the General Preface (1829) to the 'Magnum Opus' edition of the

Waverley Novels, he began work 'about the year 1805' on a novel

entitled 'Waverley, or 'tis Fifty Years Since', inspired by tales

heard from Jacobite veterans and by his own travels in the Highlands

as an apprentice Writer to the Signet (see Professional

Life). Scott was intrigued by the fictional potential of the

clash between the ancient, patriarchal customs of the Highlanders

and the march of progress in the increasingly industrialized age

of the Enlightenment. Having given the opening chapters to read

to his friend Will Erskine (portrayed, right), an unfavourable

reaction left Scott reluctant to risk the literary reputation newly

won by the success of The

Lay of the Last Minstrel (see Scott

the Poet). The fragment then lay forgotten in a drawer

until autumn 1813. Scott

did not, though, abandon the ambition to write prose fiction. According

to the General Preface (1829) to the 'Magnum Opus' edition of the

Waverley Novels, he began work 'about the year 1805' on a novel

entitled 'Waverley, or 'tis Fifty Years Since', inspired by tales

heard from Jacobite veterans and by his own travels in the Highlands

as an apprentice Writer to the Signet (see Professional

Life). Scott was intrigued by the fictional potential of the

clash between the ancient, patriarchal customs of the Highlanders

and the march of progress in the increasingly industrialized age

of the Enlightenment. Having given the opening chapters to read

to his friend Will Erskine (portrayed, right), an unfavourable

reaction left Scott reluctant to risk the literary reputation newly

won by the success of The

Lay of the Last Minstrel (see Scott

the Poet). The fragment then lay forgotten in a drawer

until autumn 1813.

Recent

critics have queried the chronology of Scott's account, uncovering

compelling textual and circumstantial evidence that Scott was actively

engaged with the novel over the period 1808-10 and, indeed, may

not have begun work on it before that time (see the Waverley page

for the relevant arguments). They have also questioned Scott's

account (in the General Preface) of the literary influences that

led him to resume his experiment with fiction. The debt that Scott

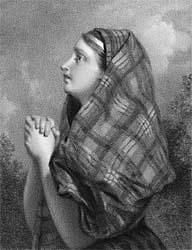

acknowledges to Maria Edgeworth (portrayed, left) is unarguably

genuine. The success of her novels of Irish manners such as Castle

Rackrent and Ennui led Scott to believe that his countrymen

might be presented to the English novel-reading public 'in a more

favourable light than they had been placed hitherto, and tend to

procure sympathy for their virtues and indulgence for their foibles.'

Edgeworth would later become a valued correspondent of Scott and

acute reader of his novels. While acknowledging Edgeworth's influence,

however, Scott downplays that of other practitioners of the 'national

tale' or novel of regional manners such as Lady Morgan, Jane Porter,

and Elizabeth Hamilton. In so doing and in backdating the genesis

of Waverley to 1805, Scott's first novel thus appears

to pre-empt rather than respond to a literary mode. Recent

critics have queried the chronology of Scott's account, uncovering

compelling textual and circumstantial evidence that Scott was actively

engaged with the novel over the period 1808-10 and, indeed, may

not have begun work on it before that time (see the Waverley page

for the relevant arguments). They have also questioned Scott's

account (in the General Preface) of the literary influences that

led him to resume his experiment with fiction. The debt that Scott

acknowledges to Maria Edgeworth (portrayed, left) is unarguably

genuine. The success of her novels of Irish manners such as Castle

Rackrent and Ennui led Scott to believe that his countrymen

might be presented to the English novel-reading public 'in a more

favourable light than they had been placed hitherto, and tend to

procure sympathy for their virtues and indulgence for their foibles.'

Edgeworth would later become a valued correspondent of Scott and

acute reader of his novels. While acknowledging Edgeworth's influence,

however, Scott downplays that of other practitioners of the 'national

tale' or novel of regional manners such as Lady Morgan, Jane Porter,

and Elizabeth Hamilton. In so doing and in backdating the genesis

of Waverley to 1805, Scott's first novel thus appears

to pre-empt rather than respond to a literary mode.

A further influence, possibly overstated by Scott, was the editorial

work undertaken for John Murray on Joseph Strutt's unfinished romance

of fifteenth-century England Queenhoo-Hall (published 1808),

to which Scott added two concluding chapters of his own. Scott

attributed the commercial failure of Queenhoo-Hall to Strutt's

excessively archaic language and desire to vaunt his antiquarian

knowledge. He felt that it would be possible to write a historical

romance more readily comprehensible to the general reader but feared

there was little appetite for tales of medieval chivalry.The enthusiastic

public and critical response to the description of Highland landscape

and manners in Scott poem The

Lady of the Lake (1810) persuaded him that a prose narrative

of more recent history, with a Highland setting, might have a better

chance of success.

Back to top

Waverley

According to Scott's account in the 'General Preface' to the 'Magnum

Opus' edition of the Waverley Novels (questioned by some recent

critics and biographers), the Waverley manuscript was mislaid

during his move to Abbotsford in 1811.

One day in autumn 1813, however, Scott claims to have come across

the manuscript in a drawer while rummaging for fishing tackle.

He reread it, was persuaded that it had potential, and resolved

to complete it. He was bolstered in this resolution by the disappointing

sales of his recent narrative poem Rokeby and

the pressing financial difficulties of John

Ballantyne's publishing business, in which Scott was silent

half-partner (see Financial Hardship).

Consulted once again on the completion of the first volume, Will

Erskine reversed his original opinion, and warmly encouraged Scott.

The second and third volumes were completed in an extraordinary

three-week burst in June 1814, and Waverley (with

the subtitle updated to ''tis Sixty Years Since'), published

on 7 July, a few weeks before Scott's forty-third birthday.

The

novel (illustrated, right) was published anonymously and, in order

to preserve Scott's incognito, the manuscript had been copied out

in John Ballantyne's hand before going to print. Scott's

novels would continue to be published anonymously or under pseudonyms

until 1827 when Scott admitted to his authorship at a public dinner.

Only those closest to Scott were let into the secret of his authorship,

though thousands more came to suspect it. There is no clear single

reason why Scott wished to remain anonymous, but a number of factors

contributed to his decision. Firstly, the novel was not considered

a serious genre at the time, especially in comparison with the

sort of narrative verse that Scott had hitherto published. Secondly,

writing fiction would not have been regarded as a decorous pastime

for a Clerk of the Session (see Professional

Life). Finally, Scott viewed the publication of Waverley as

an experiment upon the public taste and wished to protect his reputation

should the book fail. As time went on, though, and the Waverley

Novels became ever more popular, Scott's anonymity undoubtedly

also appealed to his taste for romance and mystery. The

novel (illustrated, right) was published anonymously and, in order

to preserve Scott's incognito, the manuscript had been copied out

in John Ballantyne's hand before going to print. Scott's

novels would continue to be published anonymously or under pseudonyms

until 1827 when Scott admitted to his authorship at a public dinner.

Only those closest to Scott were let into the secret of his authorship,

though thousands more came to suspect it. There is no clear single

reason why Scott wished to remain anonymous, but a number of factors

contributed to his decision. Firstly, the novel was not considered

a serious genre at the time, especially in comparison with the

sort of narrative verse that Scott had hitherto published. Secondly,

writing fiction would not have been regarded as a decorous pastime

for a Clerk of the Session (see Professional

Life). Finally, Scott viewed the publication of Waverley as

an experiment upon the public taste and wished to protect his reputation

should the book fail. As time went on, though, and the Waverley

Novels became ever more popular, Scott's anonymity undoubtedly

also appealed to his taste for romance and mystery.

|

|

Waverley was an astonishing success, the

first edition selling out within two days of publication. The

critics too were warm in their praise, particularly Francis

Jeffrey (portrayed, left) in the Edinburgh Review who

extolled its truth to nature, fidelity to 'actual experience',

force of characterization, and vivid description. Some reviewers,

though, notably John Wilson Croker for the Quarterly Review,

expressed reservations about the propriety of mixing history

and romance. Despite enduring critical doubts about its legitimacy

as a genre, Waverley marks the birth of the historical

novel in English. |

Back to top

The 'Scottish

Novels'

Over the next five years, Scott wrote a further eight novels set

in seventeenth- or eighteenth-century Scotland. It is substantially

upon these works that Scott's critical reputation now rests. Guy

Mannering (1815) and The

Antiquary (1816), Scott's own favourite amongst his novels,

complete, with Waverley, an ideal trilogy illustrating three

periods of Scottish history from the 1740s to the 1800s. Each volume

brought further commercial success. Critical opinion was broadly

favourable though there was the first hint of charges that would

be regularly leveled at Scott's future novels: that he repeated

his characters under different names, failed to make his Scots

dialogue sufficiently comprehensible for an English audience, relied

excessively on the supernatural, or was irreverent in matters of

religion.

For

his next publication Scott made a further attempt to mystify the

public, adopting the nom de plume of Jedediah Cleishbotham,

schoolmaster at the fictional village of Gandercleuch. Cleishbotham

purported to be editing the narratives of one Peter Pattieson which

in turn were supposed to be based on stories told by the landlord

of the local inn. As the volume was to be published by Blackwood

rather than Constable, Scott hoped that the public would believe

a new writer had appeared to challenge the supremacy of the 'Author

of Waverley'. Tales of My Landlord (1816) was originally

to consist of four short novels on Scottish regional themes. However, The

Tale of Old Mortality, set during the anti-Covenanting

campaign of John Graham of Claverhouse, grew to fill three volumes,

and of the other stories, only The

Black Dwarf was completed and published along with it.

The Tales matched the commercial success of the earlier

trilogy, and critics concurred with Scott's own assessment that Old

Mortality (illustrated, above right) was his best work to date.

They equally, however, shared Scott's view that The Black Dwarf,

a tale of family rivalry in early eighteenth-century Scotland,

retrod old ground. For

his next publication Scott made a further attempt to mystify the

public, adopting the nom de plume of Jedediah Cleishbotham,

schoolmaster at the fictional village of Gandercleuch. Cleishbotham

purported to be editing the narratives of one Peter Pattieson which

in turn were supposed to be based on stories told by the landlord

of the local inn. As the volume was to be published by Blackwood

rather than Constable, Scott hoped that the public would believe

a new writer had appeared to challenge the supremacy of the 'Author

of Waverley'. Tales of My Landlord (1816) was originally

to consist of four short novels on Scottish regional themes. However, The

Tale of Old Mortality, set during the anti-Covenanting

campaign of John Graham of Claverhouse, grew to fill three volumes,

and of the other stories, only The

Black Dwarf was completed and published along with it.

The Tales matched the commercial success of the earlier

trilogy, and critics concurred with Scott's own assessment that Old

Mortality (illustrated, above right) was his best work to date.

They equally, however, shared Scott's view that The Black Dwarf,

a tale of family rivalry in early eighteenth-century Scotland,

retrod old ground.

|

Few readers or reviewers were taken in by the

pseudonym of Cleishbotham, perceiving self-evident similarities

between the style of Tales of My Landlord and that of

the 'author of Waverley'. Nonetheless, in crediting his next

novel Rob Roy (1817)

to the latter, and reverting to Constable as a publisher, Scott

was diverted by the idea of bringing his two noms de plume into

direct competition. Rob Roy (illustrated, left) , a

tale of the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715, was a further critical

and commercial triumph, the original print run of 10,000, a

huge figure for the time, being bought up in two weeks. It

remains to this day among Scott's most widely read and translated

novels. The fortune of Scott's novels had by now eclipsed that

of his increasingly unsuccessful verse narratives. 1817 saw

the publication of Scott's final long poem, Harold

the Dauntless . Hereafter, he would work predominantly

in prose. |

| Scott remained with Constable for

the Second Series of Tales of My Landlord (1818), finding

that he promoted his work more efficiently than Blackwood.

The four-volume Second Series, again credited to Cleishbotham,

was entirely taken up by The

Heart of Midlothian (illustrated, right), inspired

by Helen Walker's eighteenth-century journey to London to obtain

a pardon for her sister on a charge of child-murder. Now widely

regarded as Scott's finest novel, it initially encountered

a lukewarm critical response, with the fourth volume being

generally perceived as superfluous. The public, however, remained

faithful. |

|

A

Third Series of Tales of My Landlord appeared in 1819. Written

when Scott was critically ill, The

Bride of Lammermoor (illustrated, left) was a return to

the world of the Border ballads. One of the few Scott novels to

have a tragic conclusion, its tale of foredoomed love immediately

caught the public imagination. It inspired many artists and gave

rise to numerous stage and musical adaptations, most famously Donizetti's Lucia

di Lammermoor. Its companion-piece A

Legend of Montrose, set during the Royalist Earl of Montrose's

Highland campaign against the Covenanters in 1644, has remained

somewhat in its shadow. Its mercenary anti-hero, Captain Dalgetty,

however has since been recognized as one of Scott's finest comic

characters. A

Third Series of Tales of My Landlord appeared in 1819. Written

when Scott was critically ill, The

Bride of Lammermoor (illustrated, left) was a return to

the world of the Border ballads. One of the few Scott novels to

have a tragic conclusion, its tale of foredoomed love immediately

caught the public imagination. It inspired many artists and gave

rise to numerous stage and musical adaptations, most famously Donizetti's Lucia

di Lammermoor. Its companion-piece A

Legend of Montrose, set during the Royalist Earl of Montrose's

Highland campaign against the Covenanters in 1644, has remained

somewhat in its shadow. Its mercenary anti-hero, Captain Dalgetty,

however has since been recognized as one of Scott's finest comic

characters.

Back to top

From Ivanhoe to

The Talisman

| Scott's next novel marked his first fictional

excursion outside the bounds of Scotland. Ivanhoe (1820),

set in twelfth-century England, was published under a new pseudonym

Laurence Templeton, which again fooled almost no-one. The novel

(illustrated, right) rapidly became an international phenomenon,

launching Scott's continental vogue and providing the blueprint

for the historical novel across Europe. In Britain, it played

a major role in sparking the nineteenth-century fascination

for all things medieval. |

|

Nonetheless,

Scott did not immediately seek to replicate the success of Ivanhoe with

another chivalric romance. His next two novels returned to a Scottish

setting. The Monastery and

its sequel The Abbot (both

1820) were set in the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots. If the former

disappointed many readers (including Scott himself), the latter,

dealing with Mary's escape from imprisonment, fully restored his

reputation. Its success helped Scott overcome his initial misgivings

about his ability to inhabit the sixteenth-century imaginatively,

and his next novel Kenilworth (1821)

was set in Elizabethan England. Scott, by this stage, was writing

at a feverish rate, and before the end of 1821 had published a

further novel, The Pirate,

set in early seventeenth-century Shetland and Orkney. Excluded

from the relatively limited twentieth-century Scott canon, The

Abbot and The Pirate remained amongst Scott's most popular

works throughout the nineteenth-century, providing source material

for many Victorian artists, and inspiring tourist pilgrimages to

Loch Leven (portrayed, above left) and the Northern Isles. Kenilworth too

was a major European success and, long dismissed as a succession

of historical tableaux, has recently enjoyed a critical revival. Nonetheless,

Scott did not immediately seek to replicate the success of Ivanhoe with

another chivalric romance. His next two novels returned to a Scottish

setting. The Monastery and

its sequel The Abbot (both

1820) were set in the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots. If the former

disappointed many readers (including Scott himself), the latter,

dealing with Mary's escape from imprisonment, fully restored his

reputation. Its success helped Scott overcome his initial misgivings

about his ability to inhabit the sixteenth-century imaginatively,

and his next novel Kenilworth (1821)

was set in Elizabethan England. Scott, by this stage, was writing

at a feverish rate, and before the end of 1821 had published a

further novel, The Pirate,

set in early seventeenth-century Shetland and Orkney. Excluded

from the relatively limited twentieth-century Scott canon, The

Abbot and The Pirate remained amongst Scott's most popular

works throughout the nineteenth-century, providing source material

for many Victorian artists, and inspiring tourist pilgrimages to

Loch Leven (portrayed, above left) and the Northern Isles. Kenilworth too

was a major European success and, long dismissed as a succession

of historical tableaux, has recently enjoyed a critical revival.

Scott maintained his phenomenal rate of production

with The Fortunes of Nigel in

May 1822 and Peveril of

the Peak in January 1823. With these works he returned

to the seventeenth century. The former is set shortly after the

Union of the Crowns and traces the efforts of a Scottish nobleman

to protect his inheritance at the court of King James VI and I.

The latter deals with the so-called Popish Plot of 1678. Although

Scott retained his popularity with the reading public, critical

opinion was by now divided. Increasingly, Scott was charged with

over-hasty composition, careless plotting, and the duplication

of characters and situations. Reviewers repeatedly insinuated that

he was now writing less for fame than fortune.

Two

further novels appeared in 1823. Quentin

Durward, set in fifteenth-century France, was Scott's first

fictional venture onto the continent of Europe. Despite being his

most critically acclaimed work since Ivanhoe, sales were

slow. Scott and his publishers began to fear that they were glutting

the market and that the public were struggling to believe that

the 'Author of Waverley' could be solely responsible for such a

rapid succession of novels. In stark contrast, Quentin Durward (illustrated,

above right) caused a similar sensation in France to Waverley in

Scotland and Ivanhoe in England. The vogue for the novel

subsequently spread across Europe, eventually awakening renewed

interest in Britain. Although it has fallen out of critical favour

in the English-speaking world, it remains one of Scott's most translated

works. Scott's next work St.

Ronan's Well, published after a tactical pause in December

1823, was another bold departure. His only work with a nineteenth-century

setting, it portrays the domestic tragedies and comedies of a small

Scottish spa-town and bears testimony to Scott's admiration for

Jane Austen. It was perhaps Scott's least favourably reviewed novel,

with critics censuring Scott for 'descending' to a lesser genre

befitting only mediocre talents. Two

further novels appeared in 1823. Quentin

Durward, set in fifteenth-century France, was Scott's first

fictional venture onto the continent of Europe. Despite being his

most critically acclaimed work since Ivanhoe, sales were

slow. Scott and his publishers began to fear that they were glutting

the market and that the public were struggling to believe that

the 'Author of Waverley' could be solely responsible for such a

rapid succession of novels. In stark contrast, Quentin Durward (illustrated,

above right) caused a similar sensation in France to Waverley in

Scotland and Ivanhoe in England. The vogue for the novel

subsequently spread across Europe, eventually awakening renewed

interest in Britain. Although it has fallen out of critical favour

in the English-speaking world, it remains one of Scott's most translated

works. Scott's next work St.

Ronan's Well, published after a tactical pause in December

1823, was another bold departure. His only work with a nineteenth-century

setting, it portrays the domestic tragedies and comedies of a small

Scottish spa-town and bears testimony to Scott's admiration for

Jane Austen. It was perhaps Scott's least favourably reviewed novel,

with critics censuring Scott for 'descending' to a lesser genre

befitting only mediocre talents.

| The reviewers were scarcely more enthusiastic

about 1824's Redgauntlet (illustrated,

left). Now regarded as amongst the finest of the Waverley novels,

its mixture of epistolary and narrative sequences was widely

seen as a throwback to the conventions of the eighteenth-century

novel. Set during a fictional late eighteenth-century Jacobite

Rebellion in the Border region, it is among Scott's most autobiographical

works, containing echoes of his apprenticeship to the Law (see Professional

Life) and an affectionate caricature of his father (see Family

Background). It was one of Scott's personal favourites

amongst his novels. |

|

The critics were relieved to see Scott return to

the high Middle Ages with Tales of the Crusaders (1825).

Scott here united two novels, The

Talisman, set in Palestine during the Third Crusade, and The

Betrothed, a tale of border conflicts between Anglo-Norman

and Welsh barons. Featuring Saladin and Richard the Lionheart in

prominent roles, the former gave rise to further debate on the

propriety of mingling historical facts and personages with fiction.

As Scott and his publishers had hoped, though, its virtues nonetheless

distracted critics and public from the shortcomings of its companion

piece. Particularly in Europe, The Talisman remains a highly

popular novel, though largely promoted as a work for children.

Back to top

After the Crash

| The winter of 1825-26 saw the economic recession

which led to the ruin of his publishers and to Scott's own

insolvency (see Financial hardship).

A further blow came in May 1826 with the death of Scott's wife Charlotte.

Begun before the crisis, Scott's next novel Woodstock (illustrated,

right) set during the English Civil War, was hurriedly

completed to answer pressing financial necessities. There were

renewed rumblings among the critics (unaware of the full extent

of Scott's difficulties) that Scott was writing for profit

alone but the novel sold well both north and south of the border. |

|

As Scott fought to pay off his debts during the last

six years of his life, his fictional production dropped off. His

creative energy was primarily expended on the biography of Napoleon (1827-8)

and the lucrative Tales

of a Grandfather (1828-31) and History of Scotland (1829).

He nonetheless published four further volumes of fiction. Chronicles

of the Canongate (1827) was credited to a new nom de

plume, Mr. Chrystal Croftangry, and contained two short-stories: 'The

Highland Widow', and 'The

Two Drovers', and a novella, 'The

Surgeon's Daughter'. Despite lukewarm reviews, Scott considered

the two short stories among his finest work, an opinion shared

by many recent critics. The Second Series of Chronicles of the

Canongate was composed entirely of the novel The

Fair Maid of Perth (1828). Set in late fourteenth-century

Scotland, it was Scott's last major commercial and critical success

as a writer of fiction.

Scott

returned to the fifteenth-century dynastic quarrels of Quentin

Durward for his next novel Anne

of Geierstein (1829) (illustrated, left). To his surprise,

it was relatively well received by both public and critics, though

some of the latter shared his own opinion that the factual elements

of the plot were more interesting than the purely fictional. Finally,

in December 1831, ten months before Scott's death, his last two

novels Count Robert of

Paris and Castle

Dangerous were published together as a Fourth Series of Tales

of My Landlord. The former was set in Byzantium during the

First Crusade, the latter in the Scottish Borders during the Wars

of Independence. Although Scott barely considered them 'seaworthy',

the public remained faithful. Critical reaction was uneffusive

but largely respectful, though subsequent commentators regarded

them as the weakest part of Scott's oeuvre. Scott

returned to the fifteenth-century dynastic quarrels of Quentin

Durward for his next novel Anne

of Geierstein (1829) (illustrated, left). To his surprise,

it was relatively well received by both public and critics, though

some of the latter shared his own opinion that the factual elements

of the plot were more interesting than the purely fictional. Finally,

in December 1831, ten months before Scott's death, his last two

novels Count Robert of

Paris and Castle

Dangerous were published together as a Fourth Series of Tales

of My Landlord. The former was set in Byzantium during the

First Crusade, the latter in the Scottish Borders during the Wars

of Independence. Although Scott barely considered them 'seaworthy',

the public remained faithful. Critical reaction was uneffusive

but largely respectful, though subsequent commentators regarded

them as the weakest part of Scott's oeuvre.

Perhaps, though, Scott's greatest literary commitment

in the last years of his life was in revising his fiction for the

'Magnum Opus' edition of the Waverley Novels published from 1829

onwards. In addition, Scott wrote lengthy introductions to each

volume and added copious contextual notes. The 'Magnum Opus' remained

the standard edition of Scott throughout the Victorian period and

its critical status has only recently been challenged by the Edinburgh

Edition (see Recent Publications).

Back to top

- For further details of all of the novels discussed

on this page (compositional history, plot summary, reception

by contemporary critics and readers) follow the links on the Works page.

- For e-texts of the novels discussed on this

page (from external providers), click here.

Back to Biography Index

Last updated: 23-Jan-2007

© Edinburgh University Library

|

|

Scott

did not, though, abandon the ambition to write prose fiction. According

to the General Preface (1829) to the 'Magnum Opus' edition of the

Waverley Novels, he began work 'about the year 1805' on a novel

entitled 'Waverley, or 'tis Fifty Years Since', inspired by tales

heard from Jacobite veterans and by his own travels in the Highlands

as an apprentice Writer to the Signet (see

Scott

did not, though, abandon the ambition to write prose fiction. According

to the General Preface (1829) to the 'Magnum Opus' edition of the

Waverley Novels, he began work 'about the year 1805' on a novel

entitled 'Waverley, or 'tis Fifty Years Since', inspired by tales

heard from Jacobite veterans and by his own travels in the Highlands

as an apprentice Writer to the Signet (see  Recent

critics have queried the chronology of Scott's account, uncovering

compelling textual and circumstantial evidence that Scott was actively

engaged with the novel over the period 1808-10 and, indeed, may

not have begun work on it before that time (see the

Recent

critics have queried the chronology of Scott's account, uncovering

compelling textual and circumstantial evidence that Scott was actively

engaged with the novel over the period 1808-10 and, indeed, may

not have begun work on it before that time (see the  The

novel (illustrated, right) was published anonymously and, in order

to preserve Scott's incognito, the manuscript had been copied out

in John Ballantyne's hand before going to print. Scott's

novels would continue to be published anonymously or under pseudonyms

until 1827 when Scott admitted to his authorship at a public dinner.

Only those closest to Scott were let into the secret of his authorship,

though thousands more came to suspect it. There is no clear single

reason why Scott wished to remain anonymous, but a number of factors

contributed to his decision. Firstly, the novel was not considered

a serious genre at the time, especially in comparison with the

sort of narrative verse that Scott had hitherto published. Secondly,

writing fiction would not have been regarded as a decorous pastime

for a Clerk of the Session (see

The

novel (illustrated, right) was published anonymously and, in order

to preserve Scott's incognito, the manuscript had been copied out

in John Ballantyne's hand before going to print. Scott's

novels would continue to be published anonymously or under pseudonyms

until 1827 when Scott admitted to his authorship at a public dinner.

Only those closest to Scott were let into the secret of his authorship,

though thousands more came to suspect it. There is no clear single

reason why Scott wished to remain anonymous, but a number of factors

contributed to his decision. Firstly, the novel was not considered

a serious genre at the time, especially in comparison with the

sort of narrative verse that Scott had hitherto published. Secondly,

writing fiction would not have been regarded as a decorous pastime

for a Clerk of the Session (see

For

his next publication Scott made a further attempt to mystify the

public, adopting the nom de plume of Jedediah Cleishbotham,

schoolmaster at the fictional village of Gandercleuch. Cleishbotham

purported to be editing the narratives of one Peter Pattieson which

in turn were supposed to be based on stories told by the landlord

of the local inn. As the volume was to be published by Blackwood

rather than Constable, Scott hoped that the public would believe

a new writer had appeared to challenge the supremacy of the 'Author

of Waverley'. Tales of My Landlord (1816) was originally

to consist of four short novels on Scottish regional themes. However,

For

his next publication Scott made a further attempt to mystify the

public, adopting the nom de plume of Jedediah Cleishbotham,

schoolmaster at the fictional village of Gandercleuch. Cleishbotham

purported to be editing the narratives of one Peter Pattieson which

in turn were supposed to be based on stories told by the landlord

of the local inn. As the volume was to be published by Blackwood

rather than Constable, Scott hoped that the public would believe

a new writer had appeared to challenge the supremacy of the 'Author

of Waverley'. Tales of My Landlord (1816) was originally

to consist of four short novels on Scottish regional themes. However,

A

Third Series of Tales of My Landlord appeared in 1819. Written

when Scott was critically ill,

A

Third Series of Tales of My Landlord appeared in 1819. Written

when Scott was critically ill,

Nonetheless,

Scott did not immediately seek to replicate the success of Ivanhoe with

another chivalric romance. His next two novels returned to a Scottish

setting. The

Nonetheless,

Scott did not immediately seek to replicate the success of Ivanhoe with

another chivalric romance. His next two novels returned to a Scottish

setting. The  Two

further novels appeared in 1823.

Two

further novels appeared in 1823.

Scott

returned to the fifteenth-century dynastic quarrels of Quentin

Durward for his next novel

Scott

returned to the fifteenth-century dynastic quarrels of Quentin

Durward for his next novel