|

|

Home | Corson

Collection | Biography | Works | Image

Collection | Recent Publications | Portraits | Correspondence | Forthcoming

Events | Links | E-Texts | Contact

School and University

On

his return from Sandyknowe, Scott was privately

educated in preparation for the High School of Edinburgh (now the

Royal High School), which he entered in October 1779. The School

had just moved into its new building on Infirmary Street (portrayed

left), now the seat of Edinburgh University's Department of Archaeology.

Scott initially felt at something of a disadvantage, for although

he was a year older than most of his classmates, his knowledge of

Latin, the staple of the school's curriculum, was markedly inferior.

Soon, however, he had bridged the gap and became a competent if

never brilliant scholar. He was popular with his schoolfellows who

admired his refusal to let his lameness prevent him from participating

in their boisterous playground games. The young Scott was already

a tireless walker, endlessly exploring the streets of the Old Town

and familiarizing himself with the terrain that was to feature in

The Heart of Midlothian

and Redgauntlet. On

his return from Sandyknowe, Scott was privately

educated in preparation for the High School of Edinburgh (now the

Royal High School), which he entered in October 1779. The School

had just moved into its new building on Infirmary Street (portrayed

left), now the seat of Edinburgh University's Department of Archaeology.

Scott initially felt at something of a disadvantage, for although

he was a year older than most of his classmates, his knowledge of

Latin, the staple of the school's curriculum, was markedly inferior.

Soon, however, he had bridged the gap and became a competent if

never brilliant scholar. He was popular with his schoolfellows who

admired his refusal to let his lameness prevent him from participating

in their boisterous playground games. The young Scott was already

a tireless walker, endlessly exploring the streets of the Old Town

and familiarizing himself with the terrain that was to feature in

The Heart of Midlothian

and Redgauntlet.

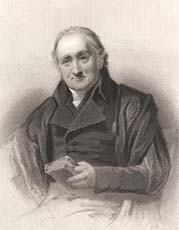

| Scott thought his first-year tutor Luke Fraser

something of a pedant. He took much greater pleasure in learning

when in 1780 he entered the class of the rector, Dr Alexander

Adam (1741-1809). Adam, one of the most innovative educators

of his age, sought to instill in his pupils not only a grasp

of grammar but a sensitivity to literary language. With Adam's

encouragement, the young Scott translated Horace and Virgil

into English verse and made his first attempts at original composition. |

|

His education was not confined to the school day. Together with

chivalric romances and the poems of Spenser, Ariosto, and Boiardo,

Scott was already a voracious reader of history and books of travel.

His father had also engaged a private tutor, James Mitchell, to

teach him arithmetic and writing (not part of the High School's

curriculum). Mitchell, a fiery defender of the Kirk, found time

to verse Scott in church history and in the travails of the Covenanters,

lessons which would eventually bear fruit in Old

Mortality.

|

|

During his last year at the High School, Scott

had put on several inches -- as an adult he was over six feet

tall -- and his family feared that he was outgrowing his strength.

Before sending him to college, they therefore decided that he

should spend half-a-year with his Aunt Jenny in Kelso building

up his constitution. He was to keep up his Latin while at Kelso

by attending the local Grammar School, picturesquely set in

the shadow of the ruined abbey (left). |

Here

he made one of the most significant friendships of his life. Among

his classmates was the son of a local shop-keeper, James

Ballantyne, Scott's future business-partner and printer of his

major works. It was also at Kelso, which was equipped with well-stocked

circulating and subscription libraries, that Scott discovered the

eighteenth-century novel, delighting in the works of Richardson,

Fielding, Smollett and Mackenzie. His most pleasurable encounter,

however, was with Bishop Percy's great ballad-collection Reliques

of Ancient English Poetry. For Scott, it was a revelation that

a distinguished scholar could share his enthusiasm for popular poetry

and consider it a subject for serious research. The Reliques

would later provide the model for Scott's first important publication

The Minstrelsy of

the Scottish Border. Here

he made one of the most significant friendships of his life. Among

his classmates was the son of a local shop-keeper, James

Ballantyne, Scott's future business-partner and printer of his

major works. It was also at Kelso, which was equipped with well-stocked

circulating and subscription libraries, that Scott discovered the

eighteenth-century novel, delighting in the works of Richardson,

Fielding, Smollett and Mackenzie. His most pleasurable encounter,

however, was with Bishop Percy's great ballad-collection Reliques

of Ancient English Poetry. For Scott, it was a revelation that

a distinguished scholar could share his enthusiasm for popular poetry

and consider it a subject for serious research. The Reliques

would later provide the model for Scott's first important publication

The Minstrelsy of

the Scottish Border.

In

November 1783, Scott was called home to study classics at Edinburgh

University. At only twelve years old, he was a year or so younger

than most of his classmates. An initial sense of inferiority was

heightened by his ignorance of Greek. With overpopulated lecture-rooms,

no tutorials, and uninspiring teaching, there was little hope of

him catching up with his peers. At the end of his first session,

Scott scandalized his Greek lecturer, Professor Dalzell, by handing

in an essay arguing that Ariosto was a superior poet to Homer. He

nonetheless became popular with his fellow students, making a number

of acquaintances which would prove influential in his professional

life as a lawyer, including William Rae, future Lord Advocate, and

Archibald Campbell, later judge of the Court of Session. Scott initially

spent two years at the College, interrupted by an illness necessitating

a further stay at Kelso. Then in March 1786, he began his apprenticeship

to the profession of Writer to the Signet in his father's office

(see Professional Life). In

November 1783, Scott was called home to study classics at Edinburgh

University. At only twelve years old, he was a year or so younger

than most of his classmates. An initial sense of inferiority was

heightened by his ignorance of Greek. With overpopulated lecture-rooms,

no tutorials, and uninspiring teaching, there was little hope of

him catching up with his peers. At the end of his first session,

Scott scandalized his Greek lecturer, Professor Dalzell, by handing

in an essay arguing that Ariosto was a superior poet to Homer. He

nonetheless became popular with his fellow students, making a number

of acquaintances which would prove influential in his professional

life as a lawyer, including William Rae, future Lord Advocate, and

Archibald Campbell, later judge of the Court of Session. Scott initially

spent two years at the College, interrupted by an illness necessitating

a further stay at Kelso. Then in March 1786, he began his apprenticeship

to the profession of Writer to the Signet in his father's office

(see Professional Life).

When

it was subsequently decided that Scott should aim for the Bar rather

than follow his father's career, he resumed his university studies.

Before taking up the formal study of Law, he attended classes in

Moral Philosophy and Universal History in 1789-90. The former was

taught by the charismatic Dugald Stewart (1753-1828) who combined

the Scottish 'Common Sense' tradition with elements of empiricism.

Believing that the true object of moral philosophy was the study

of man in society, Stewart argued that human welfare could be advanced

by following universal ideals of truth and virtue. Scott was skeptical

of Stewart's belief that irrational institutions and customs could

be clinically eliminated, maintaining that these developed in an

organic fashion and could not be uprooted without inflicting moral

and emotional damage. Nonetheless, Stewart's stress on man as a

social being, his view of society as a constantly evolving mechanism,

and his faith in universal, trans-historical values would all play

their part in the development of Scott's own philosophy of history. When

it was subsequently decided that Scott should aim for the Bar rather

than follow his father's career, he resumed his university studies.

Before taking up the formal study of Law, he attended classes in

Moral Philosophy and Universal History in 1789-90. The former was

taught by the charismatic Dugald Stewart (1753-1828) who combined

the Scottish 'Common Sense' tradition with elements of empiricism.

Believing that the true object of moral philosophy was the study

of man in society, Stewart argued that human welfare could be advanced

by following universal ideals of truth and virtue. Scott was skeptical

of Stewart's belief that irrational institutions and customs could

be clinically eliminated, maintaining that these developed in an

organic fashion and could not be uprooted without inflicting moral

and emotional damage. Nonetheless, Stewart's stress on man as a

social being, his view of society as a constantly evolving mechanism,

and his faith in universal, trans-historical values would all play

their part in the development of Scott's own philosophy of history.

|

Equally significant were Alexander Fraser Tytler's lectures

on Universal History. Tytler (1747-1813) impressed Scott with

his distrust of grandiose, universal schemes of history and

his horror of generalizations. An empiricist in the tradition

of Hume, he emphasized the role of institutions, heredity,

and environment as the shaping forces of history. Through Stewart

and Tytler, then, Scott came into contact with Enlightenment

approaches to history and sociology. In his fiction, these

would be brought to bear on the oral, folk traditions that

he had absorbed at Sandyknowe and Kelso. |

Links

Back to Biography Index

Last updated: 28-Nov-2011

© Edinburgh University Library

|

|

On

his return from

On

his return from

Here

he made one of the most significant friendships of his life. Among

his classmates was the son of a local shop-keeper,

Here

he made one of the most significant friendships of his life. Among

his classmates was the son of a local shop-keeper,  In

November 1783, Scott was called home to study classics at Edinburgh

University. At only twelve years old, he was a year or so younger

than most of his classmates. An initial sense of inferiority was

heightened by his ignorance of Greek. With overpopulated lecture-rooms,

no tutorials, and uninspiring teaching, there was little hope of

him catching up with his peers. At the end of his first session,

Scott scandalized his Greek lecturer, Professor Dalzell, by handing

in an essay arguing that Ariosto was a superior poet to Homer. He

nonetheless became popular with his fellow students, making a number

of acquaintances which would prove influential in his professional

life as a lawyer, including William Rae, future Lord Advocate, and

Archibald Campbell, later judge of the Court of Session. Scott initially

spent two years at the College, interrupted by an illness necessitating

a further stay at Kelso. Then in March 1786, he began his apprenticeship

to the profession of Writer to the Signet in his father's office

(see

In

November 1783, Scott was called home to study classics at Edinburgh

University. At only twelve years old, he was a year or so younger

than most of his classmates. An initial sense of inferiority was

heightened by his ignorance of Greek. With overpopulated lecture-rooms,

no tutorials, and uninspiring teaching, there was little hope of

him catching up with his peers. At the end of his first session,

Scott scandalized his Greek lecturer, Professor Dalzell, by handing

in an essay arguing that Ariosto was a superior poet to Homer. He

nonetheless became popular with his fellow students, making a number

of acquaintances which would prove influential in his professional

life as a lawyer, including William Rae, future Lord Advocate, and

Archibald Campbell, later judge of the Court of Session. Scott initially

spent two years at the College, interrupted by an illness necessitating

a further stay at Kelso. Then in March 1786, he began his apprenticeship

to the profession of Writer to the Signet in his father's office

(see  When

it was subsequently decided that Scott should aim for the Bar rather

than follow his father's career, he resumed his university studies.

Before taking up the formal study of Law, he attended classes in

Moral Philosophy and Universal History in 1789-90. The former was

taught by the charismatic Dugald Stewart (1753-1828) who combined

the Scottish 'Common Sense' tradition with elements of empiricism.

Believing that the true object of moral philosophy was the study

of man in society, Stewart argued that human welfare could be advanced

by following universal ideals of truth and virtue. Scott was skeptical

of Stewart's belief that irrational institutions and customs could

be clinically eliminated, maintaining that these developed in an

organic fashion and could not be uprooted without inflicting moral

and emotional damage. Nonetheless, Stewart's stress on man as a

social being, his view of society as a constantly evolving mechanism,

and his faith in universal, trans-historical values would all play

their part in the development of Scott's own philosophy of history.

When

it was subsequently decided that Scott should aim for the Bar rather

than follow his father's career, he resumed his university studies.

Before taking up the formal study of Law, he attended classes in

Moral Philosophy and Universal History in 1789-90. The former was

taught by the charismatic Dugald Stewart (1753-1828) who combined

the Scottish 'Common Sense' tradition with elements of empiricism.

Believing that the true object of moral philosophy was the study

of man in society, Stewart argued that human welfare could be advanced

by following universal ideals of truth and virtue. Scott was skeptical

of Stewart's belief that irrational institutions and customs could

be clinically eliminated, maintaining that these developed in an

organic fashion and could not be uprooted without inflicting moral

and emotional damage. Nonetheless, Stewart's stress on man as a

social being, his view of society as a constantly evolving mechanism,

and his faith in universal, trans-historical values would all play

their part in the development of Scott's own philosophy of history.