|

|

Home | Corson Collection | Biography | Works | Image Collection | Recent Publications | Portraits | Correspondence | Forthcoming Events | Links | E-Texts | Contact Literary BeginningsScott's first attempts at literary composition were made during his years at the Royal High School of Edinburgh with the encouragement of the Rector, Alexander Adam. His school years saw Scott discover many lasting literary influences: Shakespeare, Spenser, Ariosto, Percy's Reliques of Ancient English Poetry and the great eighteenth-century novel tradition of Richardson, Fielding, Smollett and Mackenzie (see School and University). After leaving school, the wages that Scott earned as apprentice in his father's office gave him the means to expand his literary education (see Professional Life). He attended performances at the theatre in Old Playhouse Close and was able to borrow more extensively from James Sibbald's circulating library. He took Italian classes in order to appreciate Ariosto (below left) and Tasso in the original, going on to read Dante, Boccaccio, and Pulci. He worked on his French too, perusing the great French historical chroniclers and the novels of La Calprenède, Scudery, and Lesage (below centre). He even mastered sufficient Spanish to read Lazarillo de Tormes, Cervantes (below right), and Ginés Pérez de Hita's Guerras civiles de Granada, generally regarded as the first Spanish historical novel.

Pérez de Hita, who interspersed his narrative with Moorish border ballads, inspired Scott's first attempt at a long narrative poem The Conquest of Grenada. Scott soon, however, consigned the manuscript to the fire. Over two decades later, however, the Guerras civiles de Granada would provide the creative spark for Scott's poem The Vision of Don Roderick (1811). It was also during his apprenticeship that Scott made his first acquaintances in the literary world. A friend from his University days, Adam Ferguson, was the son of the great Enlightenment thinker Professor Adam Ferguson. Ferguson's home at Sciennes Hill House was a meeting place for Edinburgh's literati. Here Scott met the blind poet Thomas Blacklock who permitted him to borrow at leisure from his library and introduced him to the James Macpherson's Poems of Ossian.

In the second year of Scott's apprenticeship, a serious illness led to a lengthy convalescence which was partly spent at his uncle Robert Scott's villa at Kelso. Here Scott wrote his first love poetry to 'Jessie', daughter of a small tradesman, whom he addressed with conventional gallantry as the 'Flower of Kelso' and 'Pride of Teviotdale'. Although the anxious Scott destroyed all of Jessie's correspondence with him, his sweetheart preserved his letters and poems and later confided the details of their affair to an anonymous biographer. These were edited and published by Davidson Cook in 1932 as New Love Poems: Discovered in the Narrative of an Unknown Love Episode with Jessie --- of Kelso (see Bibliography). During his second spell at University (1789-92) Scott formed a Poetry Society and joined the Literary Society where he gave papers sparked by his new-found interest in Old Norse and Icelandic literature and mythology, a passion which would later be channeled into such works as Harold the Dauntless (1817) and The Pirate (1821). As Librarian (and subsequently Secretary and Treasurer) of the Speculative Society, he further enhanced his reputation for antiquarian erudition, impressing his fellow-members with his knowledge of medieval culture and ballad-lore. During the first years of Scott's practice as an Advocate, he was employed primarily on the Jedburgh circuit and at other Border courts (see Professional Life). This provided ample opportunity to indulge the love of ballads originally kindled during his childhood stay at Sandyknowe. Beginning in 1792, Scott made annual ballad-collecting trips to Liddesdale and its environs, aided by fellow enthusiasts such as Robert Shortreed and William Elliott. Initiated with no specific end in view, the fruits of Scott's 'raids' would eventually comprise his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. |

||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

Together with his ballad-collecting, Scott made the discovery in the early 1790s of the pre-Romantic Sturm und Drang school of German poets and dramatists. Like many of his European contemporaries, Scott was excited by their rejection of neo-classical conventions, stress on subjectivity and emotional intensity, love of nature, and depiction of man in conflict with contemporary society. He began studying German in order to read the movement's leading writers, Goethe, Schiller, Klopstock, and Bürger.

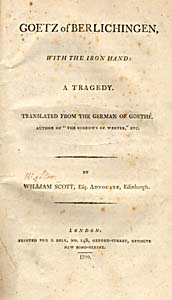

Scott acquired further works of modern German literature through the offices of Harriet, the German wife of his relative Scott of Harden who also provided linguistic assistance. Scott's approach to translation was, by modern standards, somewhat cavalier, and his shaky grasp of German grammar led to many inaccuracies. Over the next few years he produced translations of Maier's Fust von Stromberg, Iffland's Die Mündel (The Wards), Schiller's Die Verschwörung des Fiesco zu Genua (Conspiracy of Fiesco), Steinsberg's adaptation of Von Babo's Otto von Wittelsbach, and Goethe's Goetz von Berlichingen. It was the latter which most enthused Scott. He saw parallels between its robber barons and the Border reivers of his beloved ballads and first glimpsed how history could be made vividly present to a modern readership.

Lewis also helped Scott find a London publisher, J. Bell, for his version of Goetz von Berlichingen. While the volume was being typeset, a gust of wind blew some of the manuscript out of a window, and one page was lost. Lewis promptly secured a copy of the original and re-translated the missing passage. Goetz appeared on March 14, 1799, but a further mishap saw the translation attributed to William Scott. Fortunately, although Scott's Goetz was only a modest commercial success, enough copies were sold to justify a second printing with the translator's name corrected.

Meanwhile, the publication of Lewis's miscellany was much delayed. In summer or autumn 1799, an impatient Scott had twelve copies of a mini-anthology, An Apology for Tales of Terror, privately printed in Kelso by his old school-friend James Ballantyne. Along with poems by Lewis, Robert Southey, and John Aikin, this included Scott's revised versions of 'William and Helen' and 'The Chase', together with 'The Erl-King', a ballad he had translated from Goethe. Shortly afterwards, a private printing of 'The Eve of St. John' appeared. These two slim pamphlets mark the beginnings of Scott's collaboration with the Ballantyne Press which would go on to print all of Scott's major works. (For more information on Scott's relations with M. G. Lewis and his early interest in German literature, see Douglass H. Thomson's online critical edition of An Apology for Tales of Terror). Lewis's miscellany was finally published on November 27, 1800, under the amended title Tales of Wonder. Besides a reprint of 'The Chase' (renamed as 'The Wild Huntsman'), it contained another Goethe translation 'Frederick and Alice' and three original Scott compositions, 'The Fire King', 'Glenfinlas', and 'The Eve of St. John'. By now, however, Scott was deeply engaged in compiling his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, the work that would mark his true entry into the literary world (see Scott the Poet). Links

Last updated: 11-Dec-2007 |

|||||||

In

the winter of 1786-87, Ferguson's salon was the scene of the only

encounter between Scott and Robert Burns. Scott was impressed by

the plainness of Burns's manners and the independence of his judgment

but unconvinced by the humility with which he praised poets that

were clearly his inferiors. The fifteen-year-old Scott only once

succeeded in attracting Burns's attention. Burns was moved by a

sentimental print illustrating a poem entitled 'The Justice of the

Peace'. When he asked who had written the original poem, only Scott

was able to tell him it was by John Langhorne. For this, Scott received

a look and word of thanks that he would always remember.

In

the winter of 1786-87, Ferguson's salon was the scene of the only

encounter between Scott and Robert Burns. Scott was impressed by

the plainness of Burns's manners and the independence of his judgment

but unconvinced by the humility with which he praised poets that

were clearly his inferiors. The fifteen-year-old Scott only once

succeeded in attracting Burns's attention. Burns was moved by a

sentimental print illustrating a poem entitled 'The Justice of the

Peace'. When he asked who had written the original poem, only Scott

was able to tell him it was by John Langhorne. For this, Scott received

a look and word of thanks that he would always remember.